It was a clear break, for by the end of this Act all previous Acts will seem to have happened to—or have been lived by—a different person. Now on the other side of that break, yes I'm more aware of who I am and what's most important to me, than I would have been had none of it happened. In the roundabout words of Aeschylos, Wisdom comes at the price of suffering. But Aeschylos can stick a radish up his hole. By 2020's end I will prefer to have been unsuffered and unwise.

How clear a break was it? Worldwide totalitarianism coincided with a sustained and personal effort at the destruction of who I am. Both my sense of self and how I thrive in the world were on a global scale conspired against. That clear. And beginning now where Act VI left off, by this Act's end I will have had to start over, personally or professionally, 3 times in 3 years.

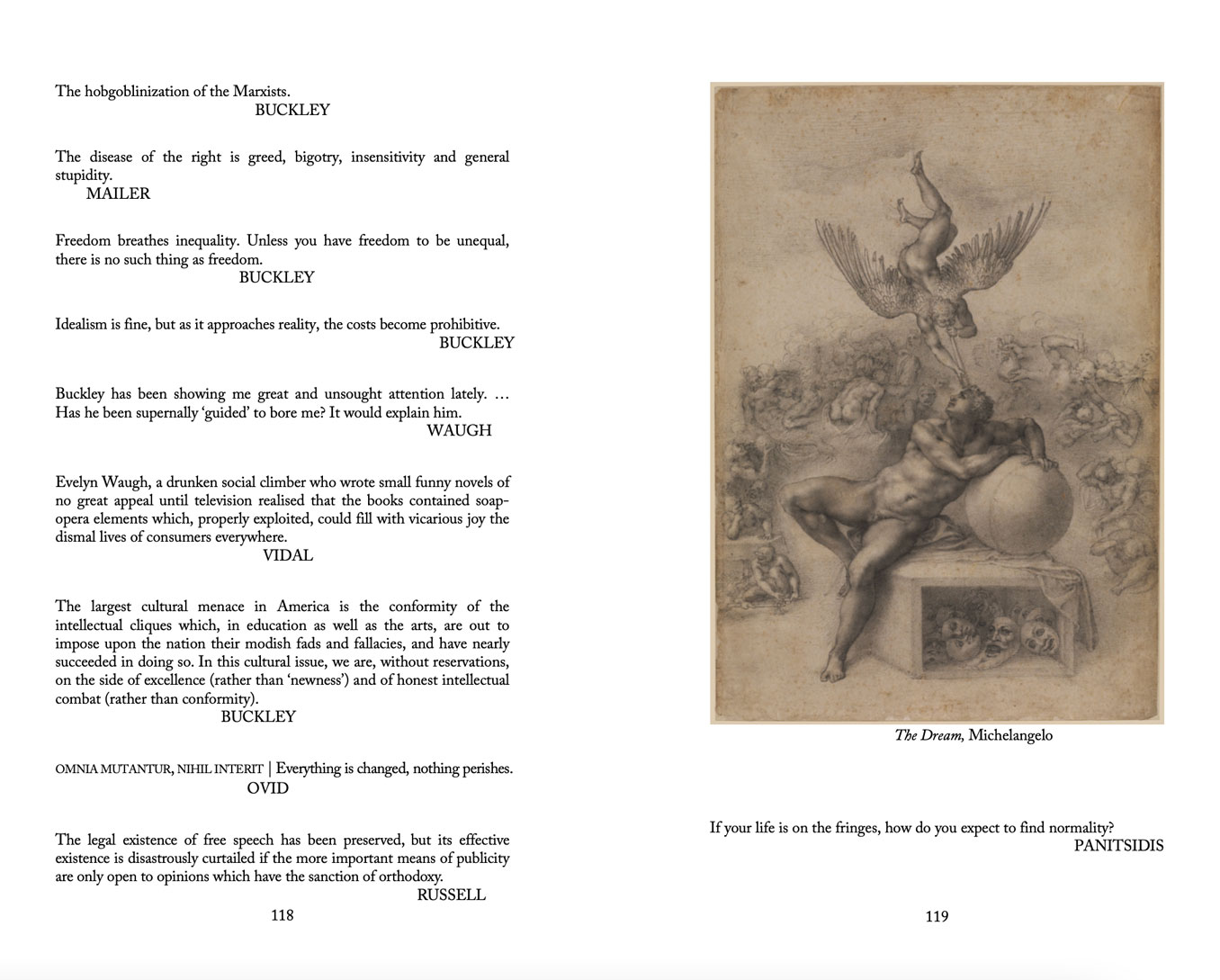

I had just released The Creative Art of Wishfulness. I had returned from my virginal visit to Greece and was not entirely looking forward to a British winter. The frustrations of being poor in London were, I thought, taking their toll on my relationship and amid those frustrations my girlfriend of 11 months started asking strange questions—questions which preoccupy the young but whose asking, when shed of the youth's self-centredness, we are supposed to grow out of. What happened with my girlfriend from 5 years ago? How many people had I slept with? What about my friend in Vietnam (whose name she knew)—when did I sleep with her?

This last rang an alarm bell, for I had never been even mildly romantically interested in my friend and other than perhaps a high-five my largest organ had never touched hers. So I asked the girlfriend why it was that she thought I had slept with my friend. She wouldn't tell me. I asked her where she was getting these adolescent questions. She wouldn't tell me. Pressed, she admitted that for months she had been receiving messages via Instagram containing a menagerie of accusations about my private past. I asked why she didn't tell me about the messages when they were sent. She said everything was good between us and as long as things were good nothing else mattered. But now that we were having trouble (trouble caused by the suspicion concocted by the messages) she wanted to know if there was truth to them.

I asked her to show me the messages. She said she couldn't. The account that had sent them had been deleted. I asked her what else this ghost account had said—she told me that they had alluded to the contents of a private conversation I had had with someone when I was in Vietnam that summer. That conversation, I remembered, had been in person. So the anonymous calumniator had either been present at it and warped it on—or had been relayed it warped version by someone who had been there. Apparently the troll was an 'expat' in Vietnam—but I had no idea who it might have been. Then I received a message from my friend in Vietnam, saying that my girlfriend had just messaged her: 'I know you and Josh slept together and I know you have a boyfriend now, but I'm totally cool with it—jealousy's not my thing.' My friend was as confused as I was about the purported sleeping-with, but she wasn't the only one being contacted. I then got a message from my girlfriend from 2016, this time with screenshots: "I know you know Josh, and I'm wondering if you could help me figure out what he's done to me?"

What I had done to her. All I had 'done' was up and move from a Vietnamese paradise to a London poverty to be with her. I had spent a year of scarce income on a few months' rent to do so. What I had 'done', was introduce her to my family and my friends in four countries. All ultimately that I had done, was exchange my beloved motorbike and unlimited sunshine for the DLR, Blackheath drizzle, and unwarranted suspicion.

Otherwise one of the loveliest corners of the earth,

Blackheath became for me, and remains, a nexus of autumnal misery.

And in exchange she was accusing me second-hand of having committed several emotional atrocities and refusing to tell me who the invisible first-hand was. She soon alleged that I had slept with my friend only a few months previously—that I had in fact cheated. So I decided that a safety valve was the best thing to inject into our strained relationship, and would fly to Bangkok to start research on The Stones of Angkor. I had so little money that I had to ask a friend to loan me the flight until I could transfer it to my debit account the following week—and back I went to Southeast Asia, to relieve the baffling pressure and to start new work.

Then it was my birthday. I didn't know very much about stalkers then, or about sociopaths, or what gaslighting was—and what little I did know I knew from her. She had done a great deal of research into them, as, apparently, her ex-boyfriend and her mother possessed aspects of all three. Earlier in the year she had told me that sociopaths ruin birthdays—that they can't stand a day that's not about them. And amid all that was going on between us, amid my being alone in Bangkok, she ignored my birthday. Not a phone call, text message, an emoticon. The next day I called her and as I walked through Wat Ratchabophit we broke it off.

She quickly started on the reprisal emails, and again I lived in fear of the notifications on my phone. But I had a new Reading Society semester to launch—in fact a Reading Society year—and I hunkered down to ensure that year's success. So obviously miserable was I that my mother flew for the first time to Southeast Asia. I showed her the temples of Bangkok, around Chiang Mai, the ruins of Angkor—and while we were in Siem Reap I received a message from another friend, who had just flown to a Thai island to attend a wellness retreat with her best friend. My now ex-girlfriend had stalked this friend's Instagram and seen that she was flying to Thailand—and had concluded that she was flying there to be with me. She messaged the friend something like: "I know you're flying to be with Josh but I thought you should know that we only just broke up, so I assume you both planned this while we were together."

The Stones of Angkor—a documentary 3 years in the making, only this year will I get the chance to complete it.

The Stones of Angkor—a documentary 3 years in the making,

only this year will I get the chance to complete it.

I was in Cambodia with my mother, showing her the temples that have for so long been a source of nourishment to her son's imagination and curiosity. And I was being accused behind my back of partaking in an oriental love-conspiracy with a friend I'd known for years. Reprisal emails I had experienced before; this was new. All I could conclude was that the break-up was hitting her harder than it was me and that she had gone slightly lopsided therefore.

A few weeks after my mother left I too flew home for Christmas and after a fortnight with family I returned to my Bangkok refuge to figure out my next move. In renewed solitude I (over)analysed what had happened in the last few months and concluded that I had been Othello'd—that somebody somewhere, for some reason hateful of me, had gone after me because of that hatred—and with a few direct-messaged lies they had tanked my relationship. But if the relationship was so easily tankable, it couldn't have been much of a relationship in the first place. I had misestimated how strongly she felt and in the last had dodged a time-wasting bullet.

It was a difficult month, that January—more difficult than the break up's November—as I was entirely alone, in my old building, on my old rooftop, and seemed to have gotten nowhere since last I was there. Despite weeks of pensiveness I could not for the life of me figure out who my Iago was, and I began to despair at perhaps never being able to find a normal relationship—even to have a love-life at all—because of the malice of an anonymous social media troll. If their hatred of me was objective, logically they were waiting to strike again. In conversation one night an Athenian friend gave me the only quotation by a living person who's not a writer that's ever made it into my Commonplace Book:

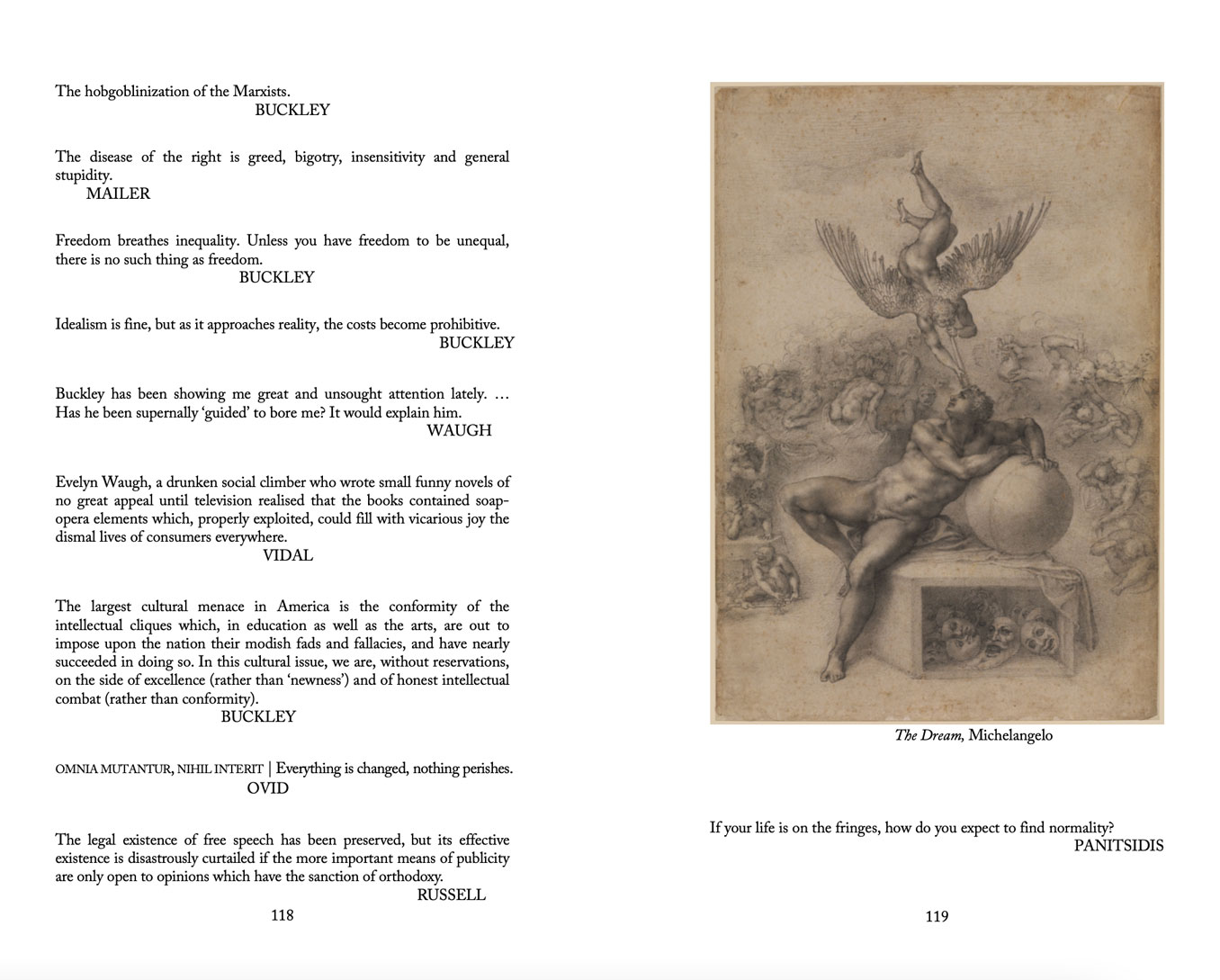

My Commonplace Book Volume 4, pp. 118-9.

(Click on the image to read the only quotation in any volume that's by a living person who's not a writer of any kind—Panitsidis.)

In order to make sense of what had happened I started automatically transfiguring the ordeal into a story. My last four books had been in some way based upon my private anguish, and though I desperately wanted to write one that wasn't, this most recent pain was too present and too vast to ignore. In 2018 I'd written a Shakespearean romcom, and had enjoyed the process thoroughly. Could I not write another—a modern adaptation of Othello, Iago a digital stalker rather than a Venetian? But that would have to wait, as my unhappy time in Bangkok was coming to an end and I needed to decide where to spend 2020.

Reasoning that Vietnam would be too painful to return to, as well as being the home of my camouflaged Iago—and wanting to stay somewhere for longer than three months—I settled on Mexico. Mexico would allow me six months of stillness and, being not-Asia, would allow me, proverbially, to create new joys and to find new loves. I started on Spanish and booked a flight to New York to visit a friend there, after which I would fly south for the Spring. A week later the flight got cancelled and refunded. It went through China, so I thought that probably that was the problem and booked another one through Japan. In New York I had two perfectly enjoyable weeks, doing nothing besides having fun with friends. We discussed what we thought was going on with this new thing called 'coronavirus' and laughed at the fact that Australia's reaction was to buy toilet paper. I left my suitcase in my friend's Greenwich Village apartment and flew to Cancun with only a backpack—intent on seeing new places, on creating new joys, finding new loves—excited to be starting over.

In Tulum I checked into a $20-a-night hovel and discovered cheladas and sopes. I planned on spending a couple of weeks there before moving inland and when eventually I found somewhere worth staying, I would settle and begin work on the next novel—that which was to be entirely unrelated to my personal pain. At a bar one night I made friends with two New Yorkers who were on vacation and I started spending my afternoons with them. One evening having the laid-back time of our lives, they both tagged me in their Instagram stories. I post almost nothing personal to my social media and to look at it you’d think I were a friendless hermit eunuch. Probably it was the weed brownies we’d just eaten that made me momentarily desire to appear normal. I tagged them in my story too.

Mexico. What was meant to have been a break from years of chaos turned almost instantly into the scene of unprecedented mayhem.

Mexico. What was meant to have been a break from years of chaos

turned almost instantly into the scene of unprecedented mayhem.

20 minutes later, at the precise moment the weed brownie wore off, both women received the same direct message from a fake & anonymous Instagram account: ‘Be careful of your friend Josh.’ I was waiting in their hotel's bar for them to get changed for dinner. They came out to ask me what this message was about. Standing in their hotel room as bewildered as they were, simultaneously they now received the same 15 messages that outlined how perfectly evil I am. My stomach sank as they read them out loud. I was a misogynist, a cheater, violent towards women—a racist homophobe and a spreader of venereal disease. My face drained of colour. Worst, or rather best, of all—I travel the world lying to women. (An inventive line, if you've read Exquisite Hours.)

These new friends had seen my $20-a-night hovel and both had held my 3-year-old cracked iPhone. If that was my shtick, they laughed, I wasn't very good at it. And all this was coming from an anonymous private account. They concluded that the whole thing was merely slander, but they had only met me a few days ago. Outside accusation instantly renders a new acquaintance suspect. Still pale from shock I said that I was leaving. Then they both got another message:

‘Message his ex-girlfriend and she’ll verify it all.'

'Oh God,' I said, and cycled back to my hovel. When an hour later my phone connected to wifi the longest night of my life commenced.

The anonymous troll had continued to urge the women to message my ex-girlfriend until finally one of them did. The ex responded immediately. There followed hours of sitting in the hovel, listening in horrified disappointment to their video recordings of the voice recordings she was sending them. She had transformed our entire courtship into the common process by which I lure my victims. She disparaged each and every member of my family, whom I had pressured to let her into their lives. She invented a series of fetishes that I’m much too uncool to possess. And while reasserting my penchant for domestic violence she assured them that she was only contacting them out of womanly solidarity—she wanted nothing more than to prevent them from being tumbled after her into the mass grave of my casualties.

I had never put so much effort into a relationship as I put into ours. It had not only all come to naught but had led to this. All the memories I thought we shared were now sources of malice to the person with whom I had shared them. Her voice was now the microphoned repudiator of a time together that only six months previously we both felt had founded a lifelong relationship. She whom I thought I had loved was either gone or had never been in the first place.

I had known these new friends for only a couple of days but after three hours of voice notes—and a catalogue of crimes that made of Hitler a Jehovah's Witness—they conceded that it was all too implausible. If anybody were as evil as she said I was they'd either be in prison or in government. She was clearly a woman scorned, hurt, and probably bored. Regardless of its implausibility I was exhausted and went to sleep. First thing the next morning I called my brother to tell him what had happened. He said nothing and started talking about something else. I said, ‘Woah, woah—is this not strange to you?’ He said, ‘I got those messages last month.’

‘You fucking what?’

‘Mum got them yesterday.’

I hung up and called my mother. ‘Mum, what the hell?’

‘Oh I just assumed it was her. We never liked her anyway—and I warned you about the Dutch.'

My sister was in the kitchen with my mum and shouted:

'The bitch messaged me too!'

She had messaged my little sister to tell her how evil her big brother was.

Sufficiently astonished, I went out to find some breakfast. I found that everything and everywhere was shuttered. Mexico was falling prey to the Australian toilet-paper panic and I started to suspect that I might not be able to stay in Mexico for 6 more days let alone 6 months. After a convenience-store coffee I cycled back to the beach to apologise to the women for all that had transpired. On my way there I realised that my wallet, and all access to any money, had fallen out of my back pocket. I retraced my route, asked every person I passed if they'd seen a wallet, walked my bicycle up and down the four kilometres of crumbled road and rubbish-lined track that I had ridden before realising it was missing. Increasingly panicked, after two hours of searching I was squinting down at a patch of leaves the same colour as my wallet when a voice sounded over my shoulder

'Are you Joshua Humphreys?'

I ignored the voice, thinking it must have been a delusion of sunstroke. It sounded again: 'You wrote Exquisite Hours right?'

I turned around and beheld a smiling brunette angel. The angel beheld a panicked and sunburnt man—who hugged her: 'You're about to save my life.'

'I am?'

'I need to borrow twenty dollars.'

When the strangeness of the interaction wore off we sat down to breakfast and I told her all that had happened in the past three months—and the past 24 hours. She was an entirely sympathetic ear, for the same reason that she loved Exquisite Hours: she had once been outright conned in a very grandiose manner by a member of the opposite sex.

Back in my hovel I sat down to figure out what the hell I should do next. I could get my brother to wire me my own money and stay in Mexico. Still I would have no bank cards, and what if everything stayed shut for months? My friends in Australia urged me to fly home. Knowing well the nature of that country I knew that to return would mean being unable to leave for years—the first of my correct predictions about the pandemic of government that the next three years became. At all costs I would avoid flying home but regardless of where I was to go next my suitcase was in New York. To get there I needed to get to the airport. I messaged the angel who had recognised me in the street. 'You're not going to believe this, but I do need to borrow $20—and I can PayPal you the money straight away.'

She laughed and asked if I was 'doing an Anaïs?'

I laughed and said, 'I wish.'

And in New York, something new and destructive to me and to the world...

Times Square locked down—the 1st of April, 2020.

Walking from Greenwich Village to Greenpoint and back, I saw not a single human being. Only supermarkets were open, and I couldn't access any money so I didn't need to visit any of them. The streets, the avenues, the bridges, the parks, were empty. Had people lost their minds? They had been told to stay home, sure, but could they reasonably conclude that the best course of action was to shut down the world? I knew instinctively that what was happening was the worst possible thing for any city, any country—any individual—to do. There are natural rules that govern economies. To disrupt those rules is hubris, in the Ancient Greek fashion—and it is to invite até, nemesis, and finally tisis. This opinion I loudly voiced in the only public forum now available—social media.

Hundreds of followers, readers who had bought every book I'd written for five years, blocked me. Those that didn't block me instantly told me vehemently to stop going outside—then blocked me. It wasn't that so few people seemed able to accept that I thought the world was prioritising the wrong information and overreacting—that in fact it had its priorities upside down—that a pandemic of government would be far worse than any virus that visibly wasn't The Plague. It was that so few people seemed able to accept that somebody thought differently from them. That trend, as we now know, was in its tiniest infancy. Governments were in those early weeks allowing large-scale Marxist protests to take place. If the virus was all that bad, surely these would have been as forbidden as solitary strolls. I needed no further proof that a 'lockdown' was not only unnecessary, but political. I would learn that year, irrevocably, that most people have little interest in using whatever intelligence they might possess. People are ruled by their prejudices, and select for pronouncement only those facts that confirm them.

Stuck in New York till I could figure out how to leave, or where to leave to, I stayed with my friend—who doesn’t have social media. Unregistered as a resident in his building, I found myself unable to leave the apartment without significantly bribing his doorman. So I spent a month indoors, in an apartment smaller than the Bangkok apartment in which I wrote Grieve. And it was then that the stalker stuff really began.

Because my friend didn't have social media my ex-girlfriend was unable to figure out where I was. This especially enraged her. She assumed that I was staying with one of the messaged-women from Mexico. In the initial lockdowns people were holding Instagram-Live parties. She began joining theirs to ask frantically where I was—warning their friends against my presence, reminding them of how malicious I am. She left 1-star reviews on all of my books on every possible platform. She had contacted the yogaclown who had threatened to sue me and was repeating emphatically her regendering of the Exquisite Hours tagline. I found out that for months she had been messaging anyone interested in The New Cavalier Reading Society to tell them it was a scam. She gave me my own personal entry on a blog devoted to surviving abusive relationships.

I was as hidden as I could possibly be—unable to leave a tiny shared apartment in a locked-down megalopolis. Still I was being assaulted on and from all sides. I felt like a caged animal and needed desperately to escape. The virus clearly wasn't the Bubonic Plague and its dangers were being so loudly repeated by politicians and the media that it couldn't possibly have been as dangerous as they wanted me to believe it was. Shouldn't I at least have the option of living freely, if not normally? Let the fearful close their cells doors in front of them, but alike let the rational lead their lives. After a month of stagnant hiding a friend in London told me that she had to fly home to Europe for a few months. I asked if it would help her if I covered her rent for a few months. And on a flight with one other passenger and seven flight attendants, I escaped America.

JFK Airport, April 24th, 2020—from where I would make my 2nd escape that year, on a flight that contained only 1 other passenger.

Assuming that my ex's harassment was based on knowing where I was, I said nothing publicly of my London relocation. There followed a month of receiving messages from people with whom I had never interacted, but who lived in New York City—all of whom had received messages from a ghost account saying that they knew I was staying with them and to be afraid of me. I had over 25,000 followers. Unable to triangulate my imprisonment this brunette woman was going through my followers individually, figuring out which of them lived in New York and which were blonde and around my age—what she was telling them was my “target demographic”—as though I were a mooching Buffalo Bill. And one by one she was messaging them.

Secretly tucked away in locked-down London, the city in which our relationship had seven months ago disintegrated, the stalking raged on and I returned to living in fear of my phone's notifications. Those came thick and fast from all quarters, including—at last—from the friend who had apparently flown to Thailand to be with me when I was in Cambodia with my mother: the ex had started her own blog about surviving abusive relationships. This woman, my age, watched a lot of serial-killer documentaries & true-crime shows. This struck me as odd—I've never understood why anyone would want so many reminders of the inhumanity of humanity. I now know that she used them as either recharge stations or instruction manuals. She told me when we first started dating that her last boyfriend had been abusive and that she’d grown up with an abusive mother. She’s probably now telling a poor love-struck bastard that I too was all the horrible things she came to believe that I was.

THE STALKER STORY

IS BEING TURNED INTO THE NEXT COMEDY NOVEL!

And it needs your help to get written...

SEE MY STALKER STORY TURNED

INTO THE NEXT COMEDY NOVEL;

BECOME A PATRON OF MY WORK;

OWN AN EXCLUSIVE SIGNED COPY OF IT WHEN IT'S FINISHED...

I was fortunate that the stalking was only ever ever digital, and I know that for women this experience is often much more tangible and far more dangerous. But she went after my business, my identity, my family—my ability to make new friends, to enjoy new places, to find new loves. We were together for a year—a year that now not only meant nothing to either of us but which she had morphed into an ordeal of constant and comprehensive abuse—a tale in which I was so wicked that it even ended with—well you'll see in a few paragraphs' time. What I thought 2019 had meant, it meant not. It now was a year wasted.

I was then, and am still, alarmed at the number of people who have been through experiences so minutely similar to mine. When I share this story I'm repeatedly returned a volley of, 'Oh that happened to me once.' To anyone who's currently going through it, or who might one day have to, the best piece of advice I can give is—ignore.

Ignore, ignore, block and ignore. Stay silent. Hunker down. What the other person is doing is most akin to a fire and it needs one thing to keep burning—oxygen. Don't give them any. Don't react, don't reply, don't intervene. Their oxygen is your pain. The harassment will stop eventually. If you curl up like a pangolin, they will get bored and find another, unsuspecting, pangolin. Know also that what they're doing is about them, it's not about you. The only thing you did wrong was, you got conned into thinking you'd found a sane person. Perhaps you ignored some red flags. But you must now be the mute wall against which they've chosen to rage. Their fists will tire, or they will break. Spend as much time as you can with people who knew you before the stalker. They'll keep in focus the true construction of yourself that you and your oldest friends know to be reality.

To anybody who's thinking, or might one day think, of contacting their ex after you've broken up: just don't. They existed before you and you existed before them. Did you send them malicious emails before you were together? Why send them once you're apart? Your journeys through this short life are no longer on the same path. You both will exist after each other, and that time is much more important. Pay people the basic courtesy of seeing them as individuals in their own right—not merely as appendages that relate only to you. It's extremely dehumanising to only view someone according to how they relate to you. They are they, and you are you. Tend to your own fucking garden, and refrain from stomping on other people's flowerbeds.

And to everybody else, don't ever listen to anything told to you anonymously. Don't read anything written that's not signed by its author. These people are life-snipers. Insidious cowards. They are knotted and charred inside. Like a sound empiricist, base decisions—live your life—on evidence, and not on calumny.

Be wary of the Dutch.

And don't trust your government. Or any government.

Locked down in London, I could only watch on as Vietnam expelled all foreigners and closed its borders. My Vietnamese friends wouldn't be allowed to work for the next 24 months. Only the 5-star resorts of Thailand were now visitable via a 39-step bureaucratic process. My Southeast Asian refuge was gone. But some countries had one set of restrictions while others had none. Either the virus was behaving differently in different countries or lockdowns were political. In London as in New York they were allowing enormous Marxist protests to take place while violently dispersing non-Marxist ones. The political nature of the pandemic continued to dawn on me blindingly.

I had long considered certain aspects of my way of life as a kind of torment, self-imposed. I often spend months doing nothing besides working and walking, isolated and alone, and I hated that aspect of what I do. I also knew the mental toughness required to endure it—and I knew that most people do not possess it. But in that summer began the successful trial of governments imposing a writer's torment on entire populations. And in that summer began entire populations embracing that torment without knowing its asymmetrical consequences. I won't mention the specific but several suicides of young people I knew or the countless grandparents who descended prematurely into dementia and death—casualties all of government and not of a virus. But for the present, I had no choice but monotony. The world was closed and I was stuck. Then the Australian production company that had optioned Exquisite Hours as a film folded—unable, due to government restrictions, to continue any of their work. My future, as my present, was disappearing.

In between raging into the void, in London I returned to playing basketball in my then-ample spare time, and to meeting old friends for drinks. I began to plan a documentary of Cambodian history—and looked naively forward to returning there soon to make them. I spent the majority of that second and longest lockdown reading. My Commonplace Book grew so quickly that 2020 has almost its own 300-page volume. I was so broke that summer that in order to eat I had to visit supermarkets half an hour before closing to find meals that were drastically marked down. As with most people, my evening walk to the supermarket was one of four that I took each day to try to maintain an asphyxiated sanity. And all the while I checked border restrictions obsessively. Italy seemed to be about to open. Eventually its convoluted restrictions were unable to clearly delineate between residents of a country, citizens of a country, and visitors from a country. After several exchanges with the consulate in Rome I was pretty sure that I could talk my way in.

Venice during 2020's first lockdown.

I was able to film my Venice Tour without a single human onscreen.

And after bluffing my way out of the UK, bluff my way in I did.

In Venice I turned my Stones of Venice Tour into a kind of virtual documentary. Previously given in person, I filmed the route and narrative as though the viewer was on the tour, seeing what we would have seen as I narrated what we were looking at. With so few tourists—in the first few days none—I was able to capture the entire city and its art & its history empty of not only tourists but of people. The uniqueness of that fortnight means that that documentary is one of my most cherished accomplishments. I then flew to Hungary to be maid of honour at the wedding of one of my dearest friends and returned to Venice to show her and her husband around as a wedding gift. Then my newest beloved opened up, too.

I flew to Athens, and as the young pandemic had so rapidly and perfectly despoiled my life I felt desperately the need to assert my own freedom. I decided to walk from Athens to Sparta, to sleep under the stars as the Ancients had done, with only my clothes for warmth and my belongings for a pillow. It was early September, and I found that I was able to do so. Walking eight hours a day, I walked from Ancient pole to Ancient pole—through the valleys and along the beaches and up and down the mountains that lay between Athens and Sparta.

In Mycenae I called my mother to tell her what I was up to. She said that my aunt, her sister, had done the same thing when she was 19—sleeping in olive groves as she hitchhiked across Greece. She said that Mycenae sounded familiar, and thought that her sister had been there—and went to the family photo albums to check.

This sister, my aunt Janette, is perhaps the biggest reason that I am the way that I am—because of her life and because of her death. A lifelong spinster, she travelled the world in her spare time and was always reading. We often stayed at her house for weekends or when our parents were away. She was obsessed with Ancient Egypt and Venice and with history, and clearly do I remember the only three VHS tapes she kept under her television: Indiana Jones 1, 2, & 3. I remember, too, the day I finally beat her at Trivial Pursuit. Encyclopaedically well-read, she always won comfortably at our family board game. When I was 17 I beat her and she left the room in livid silence. Four years later she died suddenly from two aggressive cancers. Her freedom in life, the unfairness of her death, showed me conclusively that safety is an illusion, that longevity is a fluke, that now is the time. The shortness of life that dogged us before the 20th century has been replaced by a viciousness of illness that the 21st blasts at our bodies. Like her, I could work in an office job all my life, watch my friends and siblings start families, go on trips once a year—and die suddenly a cripple before getting to see those families reach adulthood after wondering why I had wished all those days away in offices. I vowed to her on her deathbed, as she gasped for her final breaths, that never would I submit to that fate—that always would I live free. Whenever I'm inclined towards throwing in the towel, and turning to a life of investment in money, I remind myself of that vow.

Anyhow...

When my mum returned from the family photo albums to our phone call she sent me the picture that my aunt had in fact taken of Myceneae all those years ago. I said, 'Mum you're not going to believe this.'

'What?'

I turned on the video for our call, and showed her where I was standing. It was the precise spot, to the inch, from which my auntie had taken her photograph. After all that had happened, I was precisely where I was meant to be and doing precisely what I was supposed to be doing. We both started sobbing, as I now am in writing of my aunt.

From Athens to Sparta,

walked in I think 10 days—all 220-odd kilometres of it.

The final leg of that walk was the 12-hour 60-kilometre trek from Tripoli to Sparta. It turned out to be a villageless leg and thus waterless—and when at last I reached an open gas station I drank the man's fridge empty of beer. When a few days later I had recovered from all the chafing I searched for somewhere to spend the next two months. I found an apartment in a town just south of Kalamata called Verga, and there I chanced upon a Peloponnesian paradise. At the foot of a steep and immediate ascent from the sea to the mountains, I nestled in for an Autumn of teaching and of walking—every day making the 2-hour/1 kilometre ascent to the village atop the mountain behind the apartment—returning as the sun set over old Greece.

As I for some reason memorised the soundtrack to Oklahoma it was also an autumn of reflection, in which I wrote Acts V and VI of this story, and in which I meditated constantly upon how I had gotten to where I was—and how I might be able go on. My continued poverty was alleviated in Greece by the mother of the man who owned the apartment. Every other day she brought me fresh eggs and homemade bread and inordinate amounts of olive oil. Then Greece went back into lockdown. The tavernas closed, the beaches emptied, and again only the supermarkets and pharmacies were open.

The view from halfway between Lower & Upper Verga. My every-afternoon walk throughout my third lockdown.

Still the yia-yia would visit, in violation of the local lockdown. Aged well into the demographic to which covid was primarily dangerous, she also was unafraid of the virus that was the pandemic's excuse. After many discussions with her I realised why. She had lived a genuinely hard life—from youth onwards had actual things to fear, beginning with Nazi reprisals. Her attitude was similar to mine: of all the things that might befall you (stalkers, Nazis, homelessness, famine) this virus didn't warrant the compulsory and repeated cessation of all life for an unspecified amount of time. Life is short and the most precious of gifts. It ought not to be wasted in fear and indoors. In the decadent West—with only drops in dividends to frighten them—people cling fanatically to the illusion of safety. While not denying that the virus exists, and can be dangerous, talking to her I realised that functionally covid was a neurosis—something grasped onto as a distraction from the real, subconscious, problem: the emptiness and corruption of modern life. And even more so than economic conformity, people love to share, and impose on others, their neuroses.

Drowning in the old woman's homegrown olive oil, my poverty had been so crushing all year, and had come so close to meaning that I had to give up and go to Australia, that I now knew only that I needed to end it. For years people had suggested I start a Patreon but I had resisted the idea. It seemed that people used those things only to create more nonsense on social media. But I needed to stop my endless cycle of bubble and burst, of hurrying to finish projects so that I could release them—the division of my life into 6 months of writing a book then 12 months of selling it. Everybody I spoke to thought a Patreon was a great idea so I conceded and resolved to start my own. It wouldn't be a Patreon in the traditional sense—in which people subscribe to the 'content' of 'influencers'. I write and release tangible books and make watchable documentaries—works of comedic art and of history. My patrons would own those books and watch those documentaries, and 'You Write Book', as I called it, would be a kind of lay-away—in which people who would eventually buy what I create simply paid for it in tiny instalments and in advance. With whatever meagre income that might provide, I might just be able continue working without being cripplingly worried about having to get a job in a supermarket, and without—the dream—having to live off semi-spoiled food. I had a new novel to write, that which would for the first time not be based on my own anguish—and documentaries on Ancient Greek and Cambodian history to make. These, my would-be patrons would make possible in the coming year—before owning both. So the plan was.

Then, inevitably, it was my birthday again—and then it was that I heard the last from the stalker. Someone I know saw a story on Tik Tok and recognised in it my Instagram's avatar. My ex-girlfriend was sharing screenshots of our private conversations overlaid with her demented commentary on them. A year on from our breaking up, and on my 35th birthday, she was telling whatever audience she had that her ex-boyfriend—that's me, folks—had dictated to her what she had to wear, regulated what she ate, chosen what music she could listen to, decided when she slept and when she woke.

Even more than a neurosis, there's nothing that people hold so dearly as their independently reasoned-out victimhood. Perhaps my take on lockdowns and pandemics results from the same fault. But thankfully, fingers crossed, knock on wood, thumbs pressed, oracles bribed—that Tik Tok thing was the last I ever heard from her. I hope that she has found happiness somewhere, somehow, and has stopped spending her time listening to malicious trolls and drawing nonsense conclusions from social media. A friend saw her on a dating app in London at the start of 2022; I fear she may not have. I still don't know who the Ur-Stalker was—the calumniating Iago who all those months ago had anonymously messaged my girlfriend. If ever I find out who it was I shall punch them very adamantly in the face, before thanking them for nudging a Dutch bulletess so far towards insanity that I was able to dodge her.

And at last 2020 was ending. The worst and longest year of my life. It was the first year since 2013 in which I wrote no book, and its majority had been spent hiding or escaping—from Mexico, from New York, from London, and now too from Greece, for it was clear that its lockdown would last the winter. I thought that the present Act of this story was going to take you all the way through to today. It's become much too long—for I still have another stalker and two lockdowns to go, and I will come to consider applying for asylum.