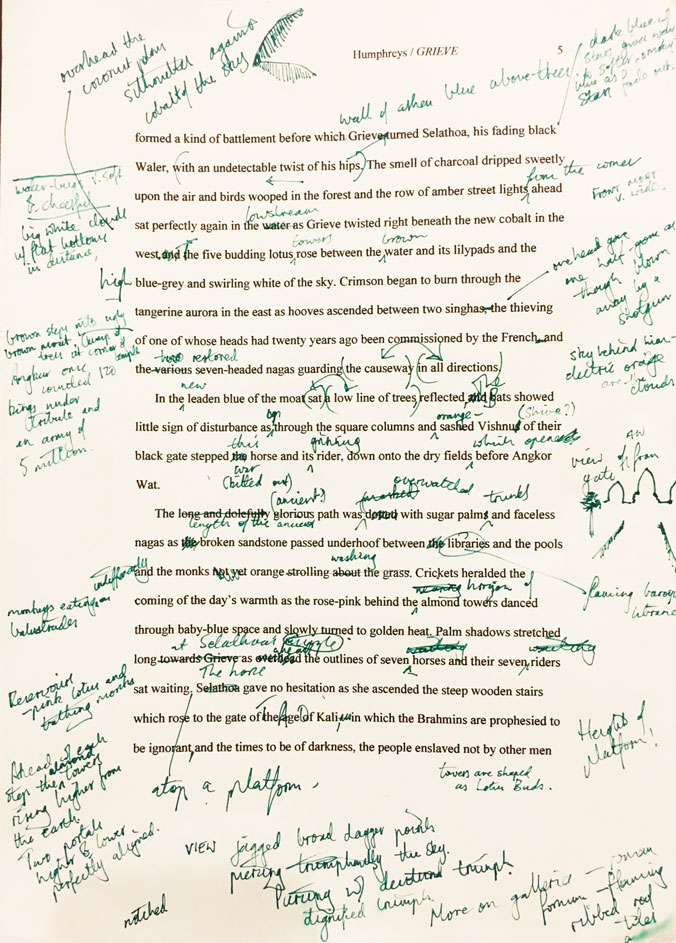

I mentioned in Act III the girl for whom I returned from Vietnam to London, our relationship swiftly ruined by the overwhelming nostasialgia which resulted from my urgent need to finish Exquisite Hours. She and I tried to rekindle things a year later but during my six weeks in Venice, giving The Stones of Venice Tour a dozen or so times, my schedule became unusual. I was up and out before the sun, slept in the afternoon, then was out for the late dinners and early-morning revelries for which Venice should be more renowned. She whose job entailed erratic working and waking hours could not tolerate my having erratic working and waking hours and instead of returning to her and London I went first to Bangkok, where the king had just died, and on to Cambodia to rewrite Grieve’s opening in Siem Reap.

I then moved to Bangkok, where and when I for the last time felt young, but again I must rewind, for I had also given the Venice tour to the people attending a wellness retreat run by a yogaclown. After the last tour of that season I wanted not at all to spend more time with said yogaclown, to whom I shall henceforth refer as Alexandra—for that's the name that her character would take in the novel soon to fall upon me like a verbose anvil. Months later moved to Bangkok, she resumed contact with me in order to say that due to the recommendation of the “digital nomad” blogs which determined her travels she too would be moving to Thailand.

The Author in Thailand: the t-shirt commemorating the king whose death and cremation would bookend my year.

After a dinner between she and I and a new Bangkok friend, the friend informed me that it was obvious that Alexandra was in love with me. I dismissed the idea, for I had said many times and adamantly that I was not interested in her romantically. But reasoning that her refusal to perceive might have been the cause of so much Venetian friction, I resolved to dispel all and any hope that she and I would ever in any way advance beyond our current professional relationship. Walking around Bangkok’s old town I asked her to describe to me her ideal partner. When she had finished I described to her my ideal woman, careful to be so comprehensive in my catalogue as to include every possible antithesis to every single aspect of her being. Then one afternoon she asked to use my building’s swimming pool. I was upstairs working in my apartment when she messaged from a sun-bed to ask where we should go for dinner. It was 1pm so I thought this presumptuous and resolved to clarify the situation once and for all. I replied, though I was not, that I was already going out for dinner with someone. Her response was, “A girl?”

I said yes, did that matter?

“Like on a date?”

“I’m not sure, she’s just a friend of a friend, we’ve already met once.”

Then came a pause of ten minutes, unusual for a woman otherwise thumb-plugged into her phone. When eventually I went to my apartment’s balcony I saw that she had taken her towel and gone home. I messaged to ask if she had left. 24 minutes later was sent a 12-minute voice-note, most of it deranged complaining that I had been leading her on, which—if my perfectly lucid statement telling her that I thought she should not move to Bangkok was anything to go by—was preposterous.

But still the plan to be employed by her on another wellness retreat, this time in Bali—for which I would supply a history of the island and its religion as well as a writing seminar—remained in place. She, she repeatedly asserted, was able to separate the personal from the professional.

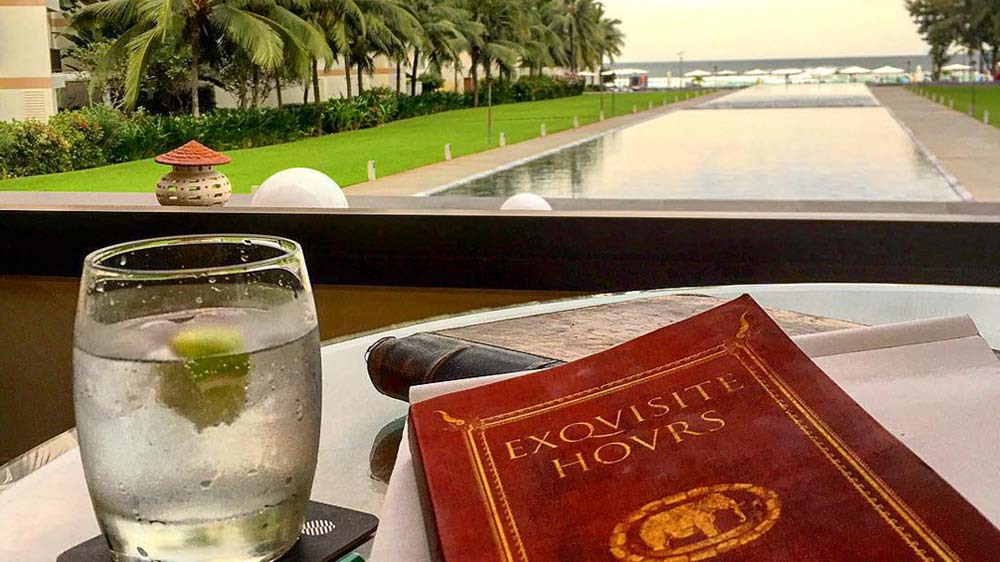

My building's swimming pool, seen from my apartment's balcony—setting of an unusually large amount of that year's work and drama.

I by then had started seeing someone who lived in Vietnam. Visiting her a second time in February, I displayed our adjacent silhouettes on social media and was within the hour sent by Alexandra another, more succinct, voice note: “Are you sure this is what you want?” I replied with a question mark and instantly was returned a long message of dismissal that was obviously pre-typed.

Fired for not being sexually available to my boss, in an instant the 12 months for which I had been the object of this woman's mania became usable fodder for a new comedy novel—and one for which I already had half the story already written. Based on my Alexandrian ordeal prior to Venice, in Venice, and until that final pre-typed message, it would be a book about a woman not un-qualified to be lecturing on "wellness", but demonstrably dis-qualified from doing so; and about the artist who must not merely suffer under her schemes but who also discovers the deceit and manipulation through which she attains the level of comfort and a peace-of-place of which he can only dream—a tranquility and security that would enable him to work fruitfully for years on end, but a comfort and calm which she uses only to bend her defects into deeper labyrinths of nonsense—and into which she lures more and more paying people.

The premise for a comedy novel if ever I’ve heard one, but, fittingly, I had not yet the peace nor the comfort in which to write it.

Then came Grieve’s release, which ended this story’s previous act. In June I moved to Vietnam to live with the girl whom I had now been seeing for half a year. There followed little more than a month of the amorous intoxication which inevitably destroys itself and, most joyously, the intoxicated too.

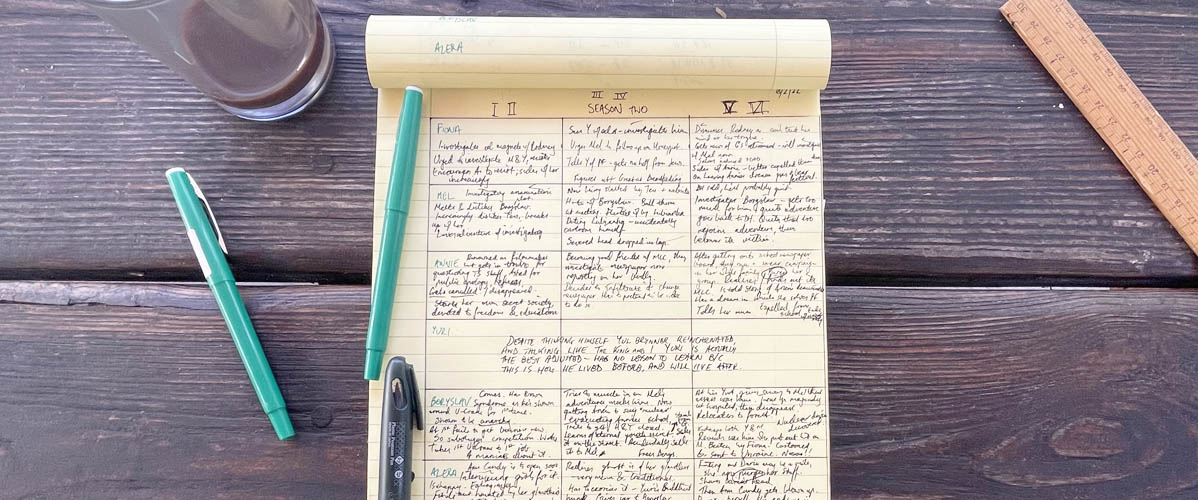

Within those blind weeks something happened that would influence and enrich my life down to the present day. Years ago I had had printed a hard-cover version of my Commonplace Book, a collection of the reading notes from my most formative years. Most days, after a long morning’s work on the new wellness story, I would read that cultural compendium in the sauna of the Vietnamese resort of which I was pretending to be a member. Then I thought that by now, six years after printing the first volume, I could probably compile my subsequent notes into a second, and began doing so. I went through all my old Moleskines, those that had accompanied me from Melbourne to London and across Britain, Italy, and Portugal and up and down Vietnam–then all the word documents and text files that had replaced them when I began living out of a suitcase—the highlights, treasures, and lustres discovered and recorded as I travelled around the world 8 times in 6 years, and the vital majority of the writing advice that had enabled me to finish 3 novels in 3 years.

Now running to 3 volumes, watch a

Commonplace Book evolve from handwritten notes into formatted troves.

As this second volume grew into a work even richer in subjects and authors than the first I realised how rare and invaluable these books were. Not just as a kind of personal reading diary, reminding me at every line of where I had been and what I was doing, but also as a unique library-in-miniature of wisdom, of advice, of philosophy, history, literature—of ideas, speeches, jokes, anecdotes, inscriptions, epigraphs, and epitaphs. Then, a year after the epiphany which led to the creation of The Stones of Venice Tour, I was given another:

What if I gave the world these books—these incomparably rich reading notes which verily were a full and clear introduction to all that was best and most beautiful in the wonderful world of culture?

As well as giving people Venice, I could give them my Commonplace Books. But the first volume existed in no digital form so I began the labour of transcribing its thousands of quotations and of preparing them for an audience. This involved photographing each page, transferring the photographs to my laptop, converting them online to text, correcting the machine’s many mistakes, returning the digitised quotations to the book’s manuscript, formatting that into a clear and readable layout.

How, though, would I give them to people? They needed explaining. Their 2500 quotations, though always attributed to authors, were largely without context; single pages often had sources as disparate as South Park and Sallust. As well the endless and profound questions which naturally arose from the quotations ought to be discussed, deserved to be discussed, had to be discussed. But how?

It would take two months of thought to come up with the answer.

While in the mornings grew the new novel’s story. I was to chronicle the frustration and despondency that accompanied the life of a painter, lived and constantly relayed to me by my brother, working as an illustrator in his own under-appreciated idiom. Bangkok was the perfect place for such a setting, for I had just spent 6 months labouring as a writer there and had had to deal with all manner of bureaucracy and incompetence. I would have this artist “discovered” by a yogaclown and, his talent recognised, asked to teach creativity on one of her “wellness” retreats. He would agree to do so because of the, to him, incredible amount of money he would he paid and the retreat would take place on a Thai island. Into that equation I would insert another woman, who attracts his attention and her ire. All that I needed to begin completing the story was the location to which my artist would travel after the retreat in order to paint his magnum opus—and to which he would be followed by woman the younger and woman the older both.

Determining that the artist would use medieval forms to explore modern problems, and positing that the apocalypse upon which medieval Christianity relied was now more than ever taking place, where, I wondered, might the medieval world still be crawling along? Where might the apocalypse best be seen? And of those countless places where might be so divisive as to act itself as a character in the story, to divide and destroy new love? Researching the world over I settled on India. Southern India. Tamil Nadu: a place whose temples seemed so exuberant as to attract any painter interested in colour, whose religion was the oldest still practised on earth, and whose squalor might be construed by some as authenticity and whose authenticity might be construed by others as squalor.

But I would have to go there in order to be able to write the place, and began planning a trip.

Madurai's Meenakshi Temple: a splendid example of the art & architecture that attracted me to Tamil Nadu as a setting for the new book.

All the while the relationship. In recounting an actual romantic relationship involving a human that (I assume) is still alive, I shall attempt to refrain from judgment and state here only facts. Our dynamic was stabbed with friction. She wished for me to do as I was told; I wished to do as I pleased. Quickly both weather-fronts met.

I do not wear a helmet when I ride motorbikes in Vietnam. I ride for the feeling of freedom which it gives me, a feeling negated utterly by the insertion of any thought to my own safety. She and I one day went on a road trip to the Loatian border and while holding me around the waist she nagged me to put on the extra helmet that she had brought along. When eventually I sarcastically agreed to, and did so only for a moment, she demanded I pull over so that she could berate me to my face. My refusal to obey her, so all the yelling informed me, was a symptom of megalomania and a delusion of divinity.

Distilled, the dialogue between us went for weeks as follows:

“Do you love me?”

“Yes.”

“Do you want me to be happy?”

“Yes.”

“You doing as I tell you would make me happy.”

“OK.”

“So are you going to do as I tell you?”

“No.”

“Then you don’t love me.”

Immersed as I am in the Ancient Greeks I have something of an idea of what Socrates (or anybody with a fully functioning brain) would have made of such syllogistic leaps.

The middle of nowhere, Vietnam:

scene of one the most delightful beratings to which I've ever been subjected.

Then, our apotheosis. Just before moving to Vietnam to be with her she demanded I stop talking to one of my best (female) friends, her reason: my friend had unfollowed her uninteresting social media account. Clearly, said the girlfriend, my friend was in love with me and did not want us to be together, was in fact offended by our happiness. Instead of refusing to do so I lied and told her that I had done as she pleased after telling my friend that in order to calm a precarious situation I would just not talk to her for a month—a course of action that did not overjoy my friend. Then one day at the beach the girlfriend and I were searching for restaurants on my phone when a notification appeared on the screen. Knowing that I was choosing to live timidly, my friend was quoting Nietzsche to me:

"The secret to the great fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of existence is: to live dangerously! Build your cities under Vesuvius; send your ships into uncharted seas!"

"The secret to the great fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of existence is: to live dangerously! Build your cities under Vesuvius; send your ships into uncharted seas!"

There followed a soliloquy publicly screamed in which she proved finally that her logical premises were envenomed and during which I reminded her that her original request had been unreasonable. She moved out of her apartment that day, I moved out of it the next. Then she began sending me long emails. Emails which aimed to turn every doubt that I had ever shared with her about myself into a certainty; emails designed to use her position as someone close to me to insert the knife as close as possible to the heart; emails threaded with a desire to make myself unknow who I knew myself to be and to forget even that I am entitled to a separate self. It was cruelty from a young woman for whom I had fallen, and for the first and last time in my nine years of wandering the world, I could not endure being alone. I flew home to be with friends and family.

Knowing quite instantly that her behaviour would be given to the younger girl in my new story, it occurred to me as I boarded another AirAsia long-haul that I was now living my books as I wrote them. This would be well, were my books stories of hope, love, and goodness. As it is, they contain only one good person, and he appears in my first novel solely to have his life destroyed because he is kind. It has occurred to me many times since that flight that I would in an overjoyed moment sit down to write a story of hope, love, and goodness—if I could find among the shrapnel but one fragment of evidence that such a place the world is.

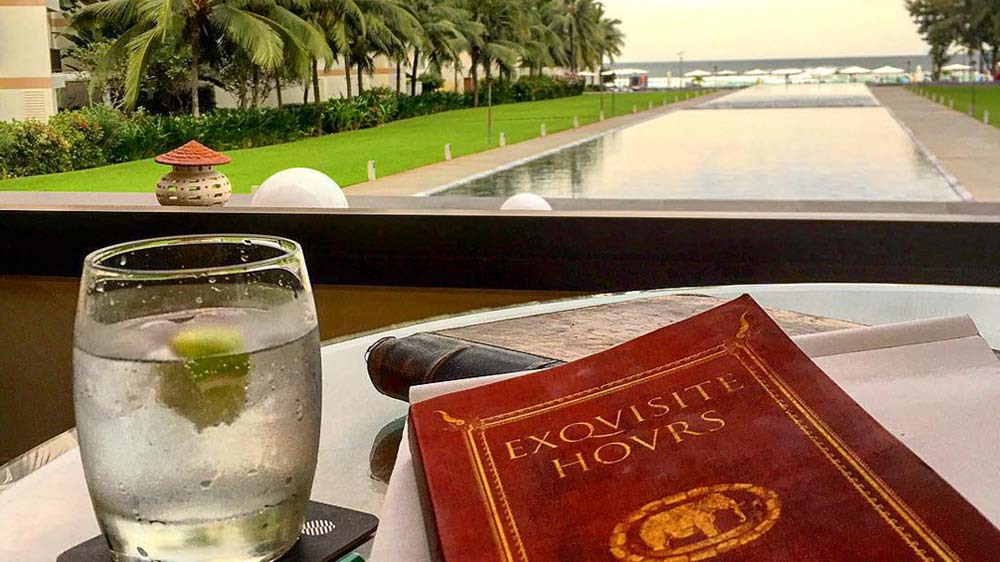

Exquisite Hours, the movie: having my 2nd novel optioned as a film was to me a vindication of my years of working, figuratively, alone and in the dark.

Home again, I received an email from a film producer based in Melbourne. She had, in the same week, seen three separate people reading Exquisite Hours and so had ordered a copy for herself, and, enjoying it rather, wished to option the novel as a film. At first I thought the email was a hoax; my dispirited corpse still was tied to the back of that ex-girlfriend’s chariot. After meeting with the producer it was happily clear that she was legitimate, and Exquisite Hours entered pre-production.

After a month of reconstructive socialising I returned to Vietnam, having decided on the format through which my Commonplace Books would be shared with the world. In two months I built that entity from scratch and opened to enrolment the first ever semester of The New Cavalier Reading Society. Ever growing in enrolment, teaching within its wide confines is to me a joy that has only increased over the years. More and more acutely I see The Reading Society as a kind of independent university. For over a decade existing in, for, and by culture I have found the rarest books, read the most tedious poems, noted down the best parts and essences of all that I’ve read as I've wandered the world. Through a years-long habit of distilling and transforming whatever I encounter into my own art, I believe The New Cavalier Reading Society houses things both tactile and literary that are in the present cultural and intellectual climate invaluable.

In encouraging habits of totally open and free discussion, in which taking offence simply isn't indulged—in exposing its members to so many forgotten writers and neglected works–in raising from the dust so many lost causes and controversial opinions—all of which are desperately rare, and in some cases illegal, in public discourse—and in endeavouring to show that Western culture is neither a corpse nor a coffin but rather a liveable, breathable, tangible, epic–an epic that frees our lives and minds—I believe that The New Cavalier Reading Society has become something that is extremely rare, beyond measure, and incomparably enriching.

I should also note here that the emails from the ex-girlfriend still were arriving in my inbox. For months I dreaded the sound of my phone’s email notification much as I imagine dissidents dread the torturer’s keys in the cell-lock. When I mentioned Exquisite Hours being optioned as a film she chose not to ignore or to congratulate but to bless—with accusations of delusion and outright lying; and to remind—that in fact she had a friend in the Canadian film industry and so knew how it all worked; to state—that no producer would option a book from someone who isn’t a real writer. Et cetera, et cetera, happy times, et cetera.

The Author in India: I despised every moment of my first 6 weeks in Tamil Nadu, and found respite only in its magnificent temple complexes.

But with tutoring duties newly assumed it was time for an Indian adventure. I bought a motorbike in Chennai and rode it to 500kms to Madurai and for the entirety of the visit comprehensively hated India. After this visit I wrote much that was unsympathetic about Tamil Nadu. Chiefly this was, I now know, because I expected it to be akin to the Southeast Asian paradises in which I had for so long lived. At first intending to take 8 weeks to ride the length of the state, I twice rebooked my flight to leave sooner, cutting it short first by 2 weeks then by another as my health from the very air deteriorated.

This is an excerpt from the diary I kept on that trip:

Kumbakonam, the 8th of November

"The room is expensive and mostly smells like scallops while the bathroom smells like celery. I walk to find a laptop repair centre and on the way pass a wet headless chicken and a wet dead calf. Mud huts are adjacent to hillocks of garbage that weep into ditches running with oily faded-green water that I could smell from 8 floors up; piles of garbage wide and low everywhere, packs of wild dogs and the buildings themselves as though abandoned after a toxic catastrophe though teeming still with people. If India is a picture of the world’s future—overpopulated and the environment literally toxic—then we are in big trouble, though this gives me many ideas for the new book."

Kumbakonam, the 8th of November

"The room is expensive and mostly smells like scallops while the bathroom smells like celery. I walk to find a laptop repair centre and on the way pass a wet headless chicken and a wet dead calf. Mud huts are adjacent to hillocks of garbage that weep into ditches running with oily faded-green water that I could smell from 8 floors up; piles of garbage wide and low everywhere, packs of wild dogs and the buildings themselves as though abandoned after a toxic catastrophe though teeming still with people. If India is a picture of the world’s future—overpopulated and the environment toxic—then we are in big trouble, though this gives me many ideas for the new book."

I recorded as many videos and took as many photographs and noted down as many odd details as I could store in my hard drive and mind, in order to soon write my new wellness novel elsewhere, for no work requiring quiet can be done in India. There was, in hindsight, a magic to the place. I waded through a flooded temple as a nadaswaram called afternoon prayers; I watched an elephant lead in procession an idol of Meenakshi to her inner sanctum; I stayed in a hilltop hotel whose grounds were stalked by peacocks, and swam in by far the most beautiful swimming pool I’ve ever seen. And among all the dead puppies and sluice-streets and overcrowded medieval Cities of Ten-armed God, I was given several incidents that would enrich and determine the story of this new comedy novel, not least of which was a Hitler-themed menswear store that decided for me the younger woman’s nationality.

Hitler Garments: the menswear store that decided for me the (Israeli) nationality of the younger woman who would follow my main character to India.

After India I went to Krabi to relax for a week, refining the new novel’s story, researching locations for its Thai-island wellness retreat, hoping that evenings of magic mushrooms would assist in forgetting as much of the horrors of India as would still allow the writing of the book. Then, returned to Bangkok, I felt intensely and unshakeably nostalgic. Apart from the success of my last novel and of the one before that being picked up as a film, and of launching ostensibly my own educational institution, it had been a year of manipulation, harassment, cruelty—a year of being used, maligned, betrayed, discarded. And I now was back precisely where I had eleven months earlier felt for the last time young. The king who had died when I arrived from Venice had lain in state a full year and now was to be cremated; his televised funeral intensified my looming sense of pointlessness.

The cure given by the first ever doctor to scientifically document nostalgia, a malady once exclusive to soldiers serving far away from home, was this:

"Create new loves for the person suffering from love-sickness; find new joys to erase the domination of the old. "

"Create new loves for the person suffering from love-sickness; find new joys to erase the domination of the old. "

I could not know it then but in a sincere effort to cure to my nostalgia I was about to spend an Australian summer, in the absence of all joy, trying to recover old love.

In the very swimming pool in which I had rewritten Grieve, pacing back and forth while trying to understand and dispel the melancholy—to push back the blurry darkness creeping in from the outlines of my mind—I had a romantic realisation. The reason my relationships had hitherto failed was that all this time I had been in love with someone. Our love had lingered for five years and so, subliminally, I had been refusing to make the sacrifices (having a regular job, doing as I was told, et cetera, et cetera, happy times, et cetera) that might have ensured the success and stability of my personal life.

I called the young woman from the pool and asked, What if I came home? What if I moved home? She said she never dreamed that such a day would come and was elated that it had. She would meet me in Melbourne and we would talk through our future.