Equally disposed to sitcoms as to sentences, having longer preferred comedy to pathos I realised that despite protracted literary pretensions still it was comedy that most set alight my enthusiasm. It was through laughter that I wished to delight.

"My real criticism is that the book owes its origins to an impulse to write a book, not this particular book. Your imagination was not so obsessed by your subject that it had to find literary expression. And that is the only way—at least while you are learning the trade—that a good book can result."

WAUGH

"My real criticism is that the book owes its origins to an impulse to write a book, not this particular book. Your imagination was not so obsessed by your subject that it had to find literary expression. And that is the only way—at least while you are learning the trade—that a good book can result."

WAUGH

As I abandoned as messy and political my third attempt at a book I saw too that though I had long had the impulse to write a book, any book—the impulse alone was insufficient. Shortly after my Eastbound epiphany not only would my imagination for the first time become obsessed by a literary subject: my ears would prove unable to escape it.

In that Chamonix sauna I had met a young Melburnian defiantly on his honeymoon, alone because he had been contacted by a woman through LinkedIn to be told that his fiancee, at a Canadian medical conference had had an affair with the woman’s husband. Denying the transgression, he presented her with evidence and upon her admission told her he was going to Europe alone.

Chamonix, where on Ruskin-pilgrimage I was told the story that would startle my ears into a new literary subject.

Two months later, studying Arrested Development in New York, I was told about a married American diagnosed with cancer who had gone home to the other side of the country to be with her family through chemotherapy. She there rekindled a romance with an old boyfriend and once in remission lied to her husband about the persistence of her ailment—so that she could continue the affair. She even kept her head shaved long after chemotherapy so as to maintain the facade.

Returned to Melbourne I was told the story of a friend’s friend who was dating a guy who had wooed her with a very distinct sequence of dates. Chatting one day to one of her friend’s friends, she was told of how this other girl was being wooed by precisely the same sequence. Both realised they were dating the same person.

So much adultery.

This new subject kept finding me, stirring my imagination—and with it I became obsessed. I asked all with whom I conversed for their worst adultery stories. The above soon diluted to only three of a dozen and all went into the subject-cauldron of my new novel. So very much adultery—and most of the offenders using their partners (or cancer), to cheat on their partners.

With my ears thusly cannonaded it would be not just any book that I would now take up to write. It was the book, my book—this book.

"The novelist has for one’s raw material every single thing one has ever seen or heard or felt, and one has to go over that vast smouldering rubbish heap of experience, half-stifled by the fumes and dust, scraping and delving until one finds a few discarded valuables.

Then one has to assemble these tarnished and dented fragments, polish them, set them in order and try to make a coherent and significant arrangement of them."

WAUGH

"The novelist has for one’s raw material every single thing one has ever seen or heard or felt, and one has to go over that vast smouldering rubbish heap of experience, half-stifled by the fumes and dust, scraping and delving until one finds a few discarded valuables. Then one has to assemble these tarnished and dented fragments, polish them, set them in order and try to make a coherent and significant arrangement of them."

WAUGH

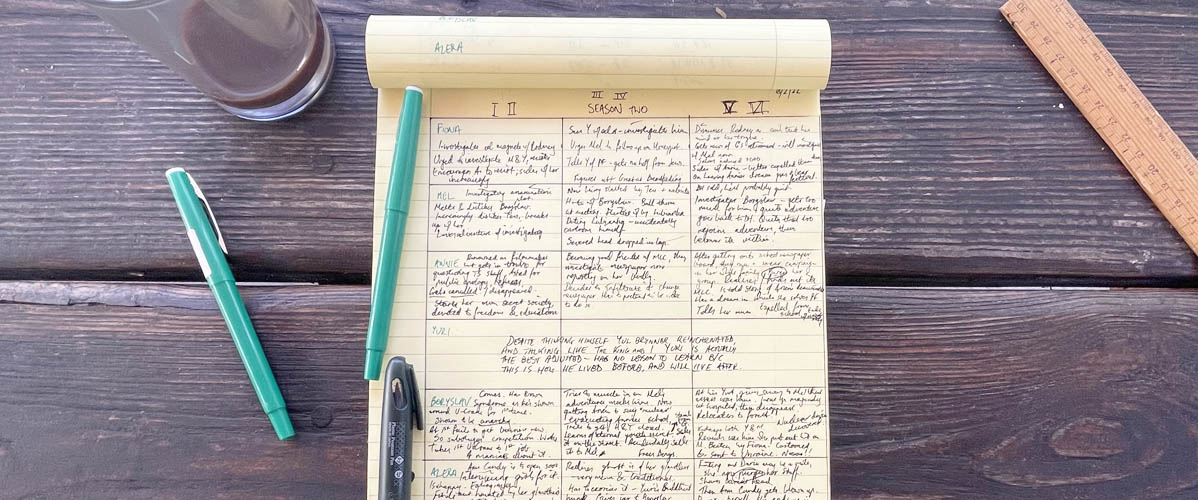

I had so quickly been given so much raw material, so perfectly incinerated, that the discarded valuables lay ready-polished for me. All I had to do was set them in order. The first notes taken towards a coherent storyline are in a red moleskine with a title-page headed, “The Uses of Love”. As I assigned the lecherous stories to individual characters their number and interconnectedness reminded me of Woody Allen’s ensemble casts, of Hannah and Her Sisters and To Rome With Love.

My highest-brow comedic influence had always been Mr Konigsberg. His eyebrows literally almost above his forehead, it was he who had sat me, as a child before an anarchic moon landing, in front of the Marx Brothers. Side Effects had led me to James Thurber and the essays of Robert Benchley. Annie Hall was the movie that validated my melancholy (and is the greatest romantic comedy ever filmed).

'...Life. Full of loneliness and misery and suffering and unhappiness, and it's all over much too quickly.'

The book’s opening then was to be a Woody-Allen-style collection of tales, set in order and significantly arranged. Significant how? The only way that a worthy novel might be: by the fate of an individual—made coherent by and according to a central human soul. Amid all this selfish cruelty, what if there existed someone not-at-all horrible—someone good even? And what if these middle-class Australian Woody Alleners, while flailing their genitals, inadvertently and unknowingly destroyed this innocent’s life?

Ultimately my new subject was not adultery but the spoiling of innocence. Untellable to children, the stories involved its gradual but constant destruction. Why not personify the virtue by turning it into a main character—into a him—and then destroy him?

So this innocent's plightful path would be the literary expression of my new subject. Still under Ruskin’s sway, two ideas must now have bubbled up from my subconscious:

"The power which causes the several portions of a plant to help each other, we call life. Much more is this so in an animal. We may take away the branch of a tree without much harm to it; but not the animal’s limb. Thus, intensity of life is also intensity of helpfulness—completeness of depending of each part on all the rest. The ceasing of this help is what we call corruption…"

"Roses and lilies would grow for us side by side, leaf overlapping leaf, till the earth was white and red with them, if we cared to have it so."

"The power which causes the several portions of a plant to help each other, we call life. Much more is this so in an animal. We may take away the branch of a tree without much harm to it; but not the animal’s limb. Thus, intensity of life is also intensity of helpfulness—completeness of depending of each part on all the rest. The ceasing of this help is what we call corruption…"

"Roses and lilies would grow for us side by side, leaf overlapping leaf, till the earth was white and red with them, if we cared to have it so."

I would call my central character Adam, the first man—innocence—and what was yet more wholesome than he? Cooperation, helpfulness, goodness—Ruskin’s flowers. The character would grow, and sing to, rare flowers, and have the latter quotation inscribed over his glasshouse.

Adam soon became an amalgamation of three grotesquely innocent people whom I had known growing up. Two autistic to the point of delightfulness, all were so thoroughly kind as to raise a suspicious eyebrow—even to Woody Allen, whose brow, as I mentioned, is already unusually high.

Adam Athelstan, innocent of fleshly things, would live with his grandmother, use “gay” in its Shakespearean sense, listen to Al Bowlly and be obsessed with ice (not the drug). Spending his days gardening and marking the passing of his year by the blooming of uncommon flowers, this messenger of gentleness and lover of beauty was to be destroyed, as humorously as I was capable of, by the adulteries of everyone around him.

Now we had a story. His life ruined, what then would happen to him?

Cefalù Cathedral. The mosaic in Latin, according to Belloc, is 'the complete doctrine of the Incarnation':— Factus Homo, Factor Hominis, 'Having been made Man, I, the Maker of Man...'

For four years I had been hopeful at the threshold of Christianity. I had knelt at Venetian altars, prayed in medieval naves from Bayeux to York, travelled to Cefalù to stand before the Incarnation—had spent years yearning to be moved, pining for religiousness, groping for conversion—verily to have my tepid soul made fervent.

It came to little.

I found much that was good in modern Christianity but very little that was great. Perhaps it was Nietzsche’s incurable influence. It seemed easy to be good—to donate canned goods and hold charitable sausage sizzles and reduce one’s morality to that of the established churches and thereby to established governments. But to be great—to really love one’s enemy and uncondemn the accused and embrace and forgive poverty and the sinner? The church seemed not necessary to be Christian.

Augustine outlines my position accurately: ‘How many who do not belong to us are really inside, how many of our own are actually outside.’ I had in history all the examples of greatness I could need. I believe that I am not exceptionally ‘bad’. I am content with being actually outside.

During those four years of groping another of my obscurer enthusiasms was J.G. Hamann, an 18th-century German mystic and anti-philosophe, of whom Isaiah Berlin said:

"To Hamann the sacred history of the Jews is not merely an account of how that nation was guided from darkness to light by God’s almighty hand, but is a timeless allegory of the inner history of the soul of each individual."

"To Hamann the sacred history of the Jews is not merely an account of how that nation was guided from darkness to light by God’s almighty hand, but is a timeless allegory of the inner history of the soul of each individual."

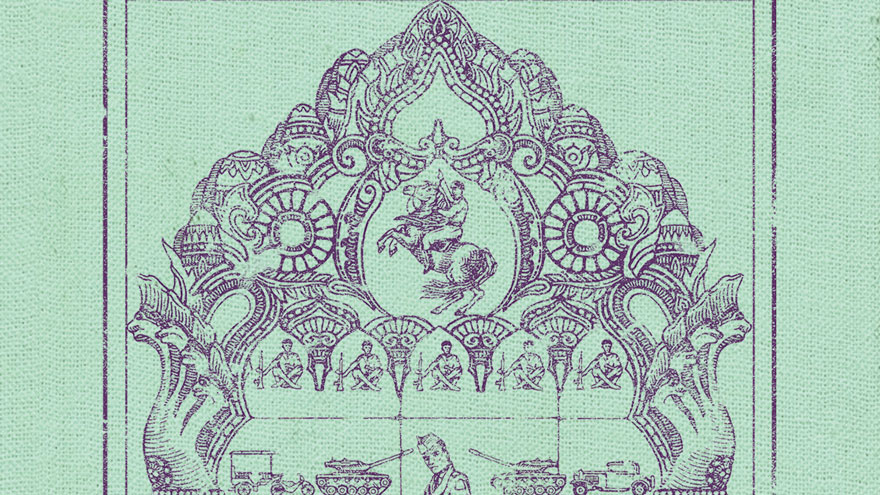

Adam’s fate, in a semi-serious attempt to embody the history of our soul, would follow the history of the Jews. Expelled from his garden he would be enslaved in the desert: mistaken for a foreign sex worker and taken to an immigration detention centre. After accidentally liberating his co-captives, his sublime naiveté would then become his vocation and my character would go from Adam to Moses to—

I knew not where, and that element would come last—though I secretly wanted to get him to Vietnam for that was where I openly wished to be.

But the novel had grown into a Woody Allen biblical epic.

I would write the thing, not just any book but this

particular book—certain to be the culmination of 4 years of literary, and a lifetime of comedic, preparation—and move to London and get a literary agent—and that would be that.

"On the first page of the file put down the outline of a novel of your times enormous in scale and work on the plan for two months. Take the central point of the file as your big climax and follow your plan backward and forward from that for another three months. Then draw up something as complicated as a continuity from what you have and set yourself a schedule."

FITZGERALD

"On the first page of the file put down the outline of a novel of your times enormous in scale and work on the plan for two months. Take the central point of the file as your big climax and follow your plan backward and forward from that for another three months. Then draw up something as complicated as a continuity from what you have and set yourself a schedule."

FITZGERALD

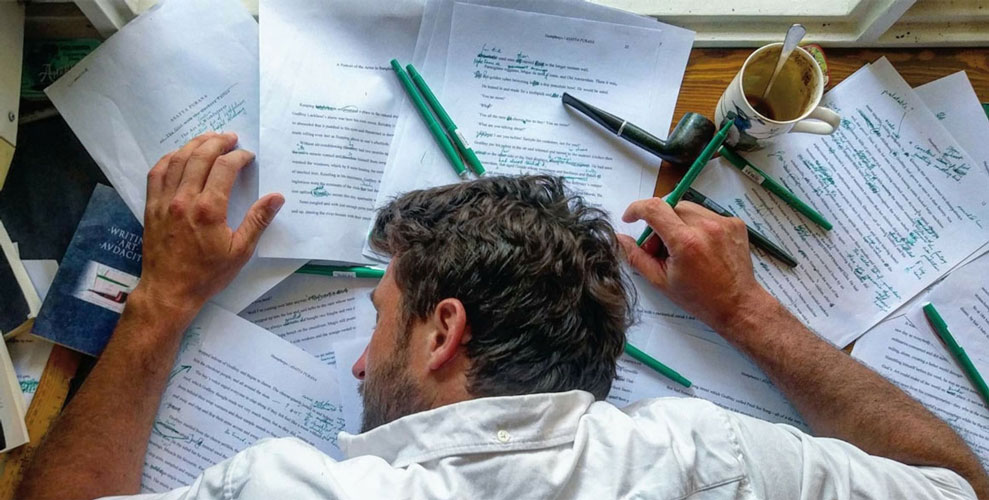

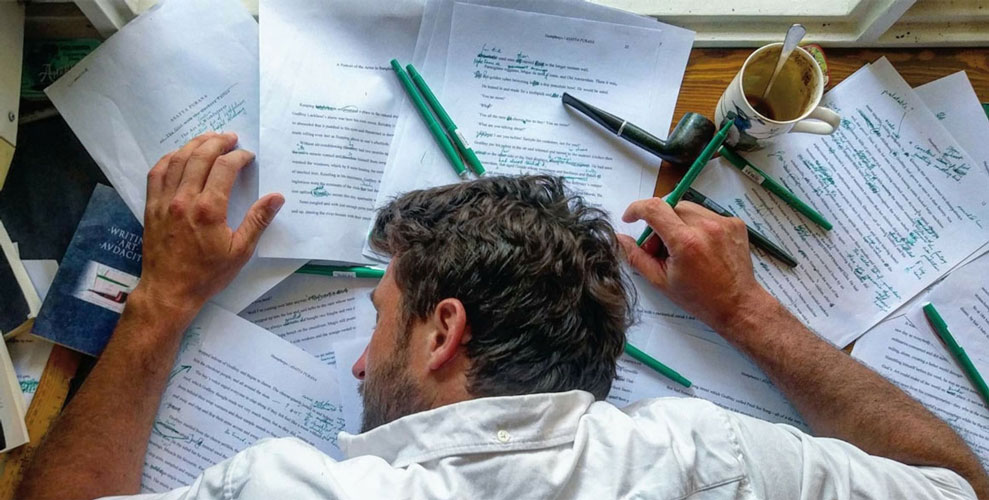

I lived at home for the two months it took for my UK visa to process and spent that time working backward and forward on the story’s plan. With twelve characters conducting affairs plus their several victims and Adam, there was much weaving to be done. But so I toiled, meticulously—a hermit at 28.

Hardly starving, Hemingway had a trust-fund income of $40,000 a year while in Paris. It is money that makes writers and not the other way around.

The Scuola di San Rocco, where Anaïs would be humanised, and shed her first tear in years—and from a description of which the book's title was taken.

Everyone I knew was working towards promotion, parenthood, picket fences. I had fallen to wandering the world, collecting stories, gallivanting much. I had made and spent three miniature fortunes in order to undertake what Hemingway called the full-time job of learning to write prose. Early in my reading I was struck by a detailed accounting of Ernesto’s years in Paris. Now seen commonly as a starving—the starving—artist, his first wife had two trust funds which when adjusted for inflation gave him $40,000 a year.

The bastard.

"I remind myself that I must take some work as the whole end of life and not think as others do of becoming well off and living pleasantly."

YEATS

"I remind myself that I must take some work as the whole end of life and not think as others do of becoming well off and living pleasantly."

YEATS

It seemed that money made writers and not writers that made money. Nearing the end of my third fortune, I knew this new book would swallow the last of my savings. It is a theme that has been precisely repeated four times in my career. But I had taken the writing of comedy novels as the whole end of life. There was then no sense in thinking of living pleasantly or of becoming well off.

Instead I had stood up to live—had been married and divorced, repudiated an adolescence of nefarious friendships, worked 90-hour weeks for months on end solely to save enough money to be able to really work. I had crowned my education with a honing of Ruskin’s lessons across two trips to Europe and since discovering my vocation had prepared the ground for no other thing than writing.

I could, even to Thoreau, sit down to write my Woody-Allen biblical epic.

And so I would, in Vietnam, where alone I knew the rest of my savings could secure the seclusion needed to get the first two-thirds of a book written.

I returned to Hoi An, and to the guesthouse in which Sam and I had passed that typhoon, and after a week of overdue gallivanting I settled into the labour of Adam’s story.

"Waugh began Scoop in October 1936. The first two chapters were written in a fortnight, and deemed by him ‘light and excellent’. By July 1937 he decided it had to be ‘entirely rewritten’. It was finally published in May 1938."

PASTERNAK-SLATER

"Waugh began Scoop in October 1936. The first two chapters were written in a fortnight, and deemed by him ‘light and excellent’. By July 1937 he decided it had to be ‘entirely rewritten’. It was finally published in May 1938."

PASTERNAK-SLATER

I wrote ‘Light & excellent’ over my desk as Tintoretto had inscribed Michelangelo and Titian above his. Waugh had taken ten days to write the first 25,000 words of Vile Bodies and 'two chapters in a fortnight’ was something of the pace I now set for myself. I had a flight to London in six weeks and 60,000 words to write: minus days lost to hangovers and block, 2000 a day—a manageable amount.

And during these six weeks, finding in rural Vietnam an ideal working environment, I developed my writing routine.

Year-round there the days are divided evenly between light and dark. With the morning begins a torrent of scooter traffic whose horns serve as one’s 6am alarm. It's too hot to lie in bed much beyond that so I rise with the sun. The rural landscape is pleasant enough to make a pre-work stroll an exercise in curious aesthetics. The village streets are alive with children, puppies, chicks—with life: an essential presence to a comedian attempting to take a few things seriously. Theirs is a delicious style of coffee requiring no machines or cafes, their breakfasts are small and easily taken. They do not persecute pipe-smoking or preposterously tax tobacco.

It was on that first writing-only trip to Vietnam that I developed, honed, and perfected the writing routine that still enables me to finish a novel in a year.

When quickly I disciplined myself to ignore the place’s inherent distractions (chief of which in Hoi An were the pulsing of jackhammers and the garbage truck like an ice-cream van heralding its route) I was at my desk for six hours straight, the clarity of my mind each day fading, routinely and conveniently, with the nearing of 3000 typed words—the average speed at which I still write first drafts.

The exhilaration that spring of cycling to the beach every afternoon, having spent the day writing—having mastered distraction and defeated reluctance—was a feeling I have never quite recovered. There was then a line of buoys 200 metres out in the ocean. Banyan Bar had not yet closed. Each day I would arrive to an unopened bottle of Larue and after swimming out with it in hand, plop myself into a buoy. I would open the beer with my teeth and float happily in the sunshine, knowing no other thing than that I had done my day’s work to its and my utmost.

This was also the sojourn on which I first began to explore central Vietnam. It saw my first time on a motorbike, riding the Hai Van pass to Hué, out into the countryside, twice following Hoi An’s Thu Bon River into the mountains solely to discover new wonders—water buffalo before fading plaster churches, paddle-steamers turned to restaurants, endless fields of richest green and skies of searing blue.

Quang Nam province possesses an unbroken 30-kilometre stretch of white sand, most of it then unspoiled—an idyllic post-work location.

Then came London.

When I landed I again needed to do paid work in order to recover the thousands of dollars that had been exchanged for my 60,000 words. Through a Londoner friend I in one weekend found a job and a room, and Battersea became the theatre of my life and seat from which I would write the book’s final section.

Only a few weeks out of Asia I began really to miss Vietnam. The heat, the paddies, the jungle, the nights, that coffee. This nostasialgia, a longing for Asia as home, feels, I imagine, much like the impulse of a criminal. To bulge under the warmth of tropical sun, to move fast in freedom, be enclosed by bamboo-rustle—even the choppy village loudspeakers. It all feels so good in the remembering that it cannot but be a transgression, and one to which all sense might on a whim be sacrificed.

Hounded by it, for months I cooked only Vietnamese food, drank only Vietnamese coffee, rattled on about how much better everything was in Vietnam—and I watched over and again The Quiet American and Apocalypse Now. The former’s prologue (not taken from Greene’s novel) I still know by heart and in Michael Caine’s voice:

"I can’t say what made me fall in love with Vietnam—that a woman’s voice can drug you; that everything is so intense. The colors, the taste, even the rain. Nothing like the filthy rain in London. They say whatever you’re looking for, you will find here. They say you come to Vietnam and you understand a lot in a few minutes, but the rest has got to be lived…"

"I can’t say what made me fall in love with Vietnam—that a woman’s voice can drug you; that everything is so intense. The colors, the taste, even the rain. Nothing like the filthy rain in London. They say whatever you’re looking for, you will find here. They say you come to Vietnam and you understand a lot in a few minutes, but the rest has got to be lived…"

Apocalypse Now struck a deeply primitive chord within me, not as a story or a work of art (which it consummately is), but as a strange and uncontrollable sign of my love for that country. In one viewing, as those helicopters valkyried in and door-gunners sprayed villages with bullets—I cried. Dear to me were the conical hats, an aspect of home the stilt-huts, bridges in my paradise those strafed by Robert Duvall. And their destruction brought me to tears.

Sharing my enthusiasm for the film with anyone who would suffer it, I realised the story was iconic enough to be adapted for my new book. Adam’s life and floral livelihood destroyed, escaped from the desert—he still needed a new vocation and somewhere strange and wonderful for it to play out. Why not send him up a Vietnamese river? But for what reason?

Over three trips to Hoi An I had grown to dislike most of its tourism industry. The older tourists fed the place’s corruption while comparing it unfavourably to Bali. The younger used Hoi An to more affordably drink themselves to vomit. There were those who thought it a terra nullius for the depredations of yoga and anyone I spoke to staying longer than a week admitted to having run away from shortcomings whose mention would stray to judgment.

I would send Adam upriver to rescue them: make of him a David with the kingly vocation of returning gone-native tourists to their families.

Hoi An, from whose enchantments I would have my autistically innocent protagonist rescue lost tourists.

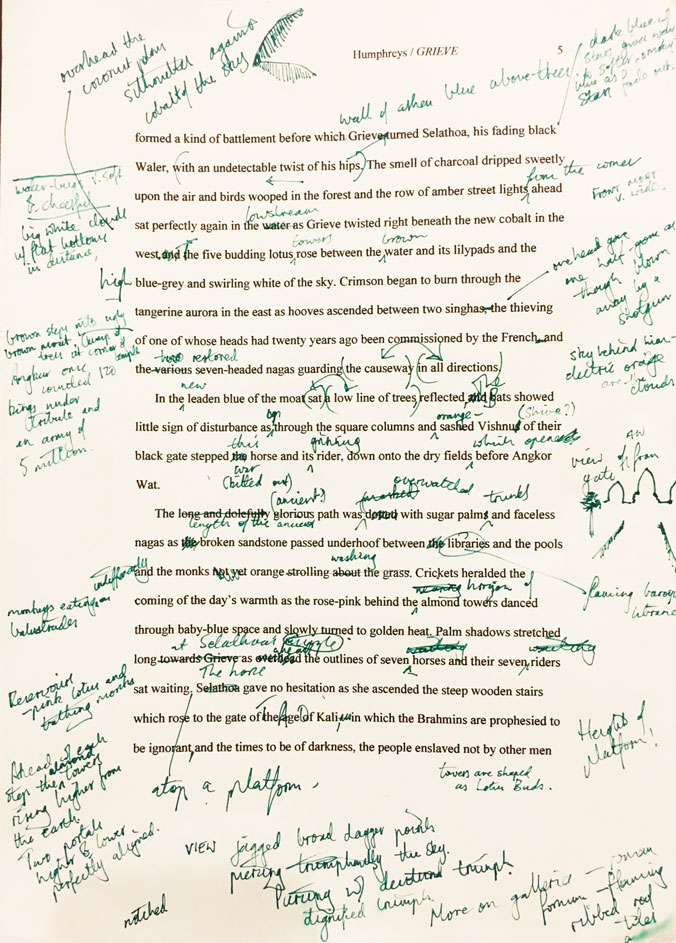

My writing routine transplanted to London and with the music of that Hoi An garbage truck as my alarm tone, I wrote the final section in a fortnight of mornings then set about the long and intense process of rewriting which novel-writing actually is.

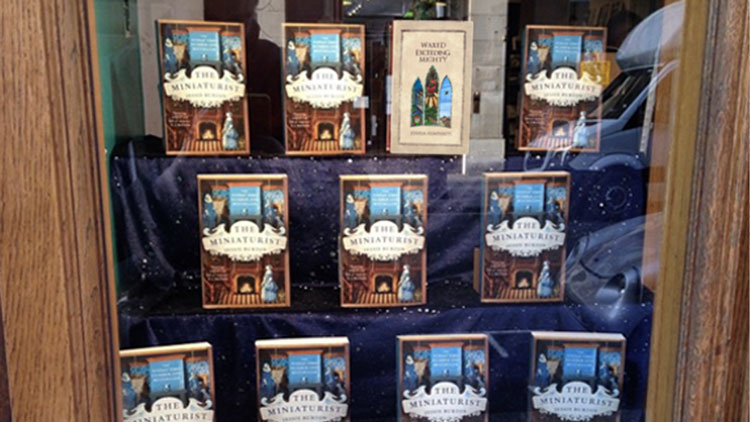

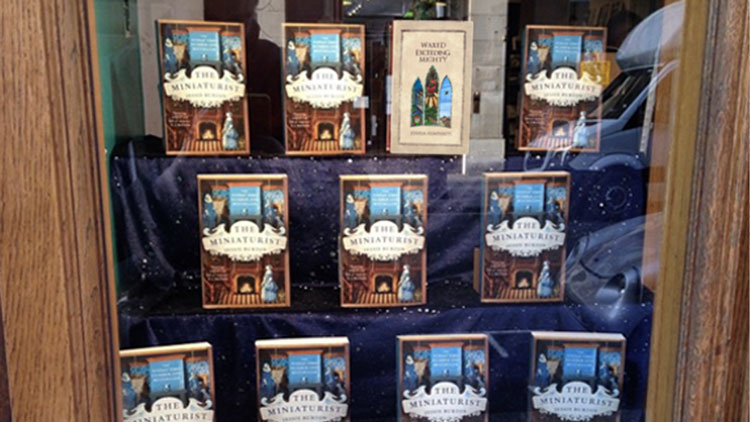

I found a title in the Book of Exodus, the adulterous ruiners of Adam’s life standing for the proliferate children of Israel, and three months later gave the finished manuscript of Waxed Exceeding Mighty to a contact in publishing. She described it as ‘page after page of beautiful writing.’ I prepared it for submission to the handful of literary agents who stated they wanted books that made them laugh. Two months went by and I heard not a personalised word.

Did they not realise what they had in their hands? Waxed Exceeding Mighty was not just any particular book, this was the book—this

book—born of an imagination obsessed by its subject, written by someone who had stood up to live before sitting down to write, who had spent years and fortunes honing his style before at last applying it to the form most expressive of his personality. Too, it was literature made hilarious.

This book had to be read.

As the year neared its end and still nothing from agents, I thought perhaps I might get it read myself. I knew that I certainly had to get it read, my sole desire being to delight through laughter, people's amusement my duty, a destiny not only to write funny books but very much to have them read.

''If I am silenced, I will make the silence audible."

KRAUS

''If I am silenced, I will make the silence audible."

KRAUS

I had heard of self-publishing. I looked deeper into it and saw that indeed it meant that any and all hacks could put into print their screed and call themselves writers. But I was far from a hack and Waxed Exceeding Mighty was anything—everything—but screed. Admittedly to self-publish would be to condescend. So was to submit the worth of one’s work to an uninspiring and humourless literary establishment.

Karl Kraus had for 25 years single-handedly written and published his own satirical journal. Doing so had only heightened his contemporary esteem. He could be enslaved to no public organ; his voice was always his own. He could write whatever he wished, whenever he wished to write it. Self-publishing did not necessarily mean delusions of talent nor inferiority of writing.

It meant freedom.

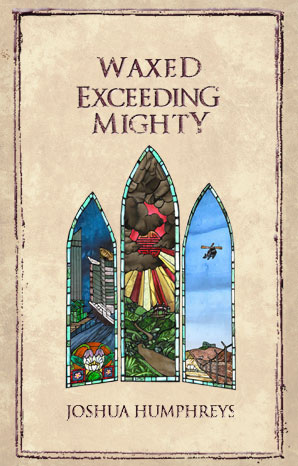

So I commissioned from my brother a cover of three stained-glass panels, one for each section of the story—Melbourne and Adam’s glasshouse, the Victorian desert and detention, Hoi An and its tropical river—and would get the book read.

The stained-glass panels on the book's cover, beautifully executed by Samuel Humphreys

To do so would need promotion. Literary agents openly asked for an elevator pitch and a tagline. To easily convey it to an audience I would need to distil the work into its essence.

What, essentially, had I written?

Divided into three books, each was markedly different. The array of adultery stories were inspired by, and interconnected like, a Woody Allen romantic comedy. Adam’s enslavement and his desert exodus were intentionally biblical. His vocation in going up rivers to rescue gone-native tourists had sprung from my time in Vietnam and from the war films which showcased the country's beauty.

I had, in nine months, written a Woody-Allen Biblical-Epic Vietnam-War novel.

Denied access to the mainstream reading world, I resolved that this Woody-Allen Biblical-Epic Vietnam-War book would enter it by force, and in doing so subvert it. The ultimate aim of any book is to appear on bookstore shelves. The only thing preventing that from happening were the unfunny economists who called themselves literary agents—what Tim Ferriss condemns as any industry’s ‘gatekeepers’.

Gates kept, I would put the novel into bookstores myself. My travels had amassed something of a social media following. I would put the novel onto bookstore shelves and implore those followers to steal it.

Thus was born #stealthisnovel.

Through a London winter I smuggled signed copies into bookstores, photographed their place on the shelf, and implored followers to by stealing them become readers. The phenomenon spread to prominent London art galleries then to Paris, Hanoi, Melbourne, Venice, New York—and Waxed Exceeding Mighty became the premature birth of the comedy novel.

Steal This Novel. I smuggled copies into bookstores, sometimes into shopfront displays, and invited my followers to steal them.

I recently retouched the book's text and, five years after its writing, found only a little that was superfluous and much that is enjoyable. It has passages which betray a writer attempting to show his competence before telling his story but it was a vital step in the refinement of my style and in creating the work that would succeed it.

Adam’s misadventure has readers who say it is still their favourite of my books. I am told that it has an energy to its structure that would later be replaced by a more elegant writing style. It’s on the worldwide Amazons with about thirty reviews and a four-star rating. As a story it is shocking, touching, and amusing. As a novel, thankfully, it is light and excellent, and—I think—delightful.

When #stealthisnovel wound down I went again to Venice and for the first time to Harry’s Bar. Without asking their price I ordered two Bellinis. When the bill came, and my astonishment subsided, I looked around at all the people vastly more able to afford two Bellinis and thought, ‘Do I have to pay this bill? If I really wanted to, could I get one of these people to pay it for me?'

The question was what I call a ‘lightning bolt’. From these moments might whole lives be uprooted, futures decided—and entire novels conceived. They're the inspirational flashes without which I don't think books worth reading can be written.