The writerly adventures of Joshua Humphreys.

Act I — BECOMING A SERIOUS MAN

I have always written, and I have always written comedy.

And the third most frequent question I’m asked is, ‘When did you start writing comedy?’ The answer is simple. When I hijacked my high school’s wikipedia page and became thereby a folk hero.

No feeling in my pimply Dylan-obsessed Age-of-Empires-playing life had yet come close to sitting in the school library and overhearing people laugh at what I had written, repeat aloud my jokes, agree with the ridiculousnesses that I alone had pointed out.

Six years later, I was in rehearsals for a comedy play that I had written and was directing and acting in, for the Melbourne Fringe Festival. A few months from opening, a cast member brought into rehearsals a copy of A Handful Of Dust by Evelyn Waugh. During a five-minute break I picked up the book and started reading. Immediately I knew that I held in my hand the highest comedic art. Its opening lines still make me smile:

‘Was anyone hurt?’

‘No one I am thankful to say,’ said Mrs. Beaver, ‘except two housemaids who

lost their heads and jumped through a glass roof…’

Smarter, more elegant, vastly more subtle and ingenious than the frivolous tenor in which I was working—in a single page I had discovered my vocation. For 2 years I had been doing stand-up, making short films, putting on sketch-plays. Python-obsessed, frivolity was not yet to my mind a vice.

I would write comedy, be a comedian. But a buffoon—not if I could help it.

I called the Fringe show off and was to set about writing a novel. About what? I had no idea. How? I hadn’t a clue, and my first order of business was to undo the damage done by 4 years of a history degree. The only 2 pieces of writing advice I recorded until that year are from Alexander Pope and Bertrand Russell:

‘True ease in writing comes from art, not chance,

As those move easiest who have learned to dance.‘‘A style is not good unless it is an intimate and almost involuntary expression of the personality of the writer, and then only if the writer’s personality is worth expressing.‘

But I would begin with imitation. Who had Waugh read when he was my age? Who formed his mind? If I read them they would form from my personality a skill comparable to his. Beginning with Firbank, Wilde, Wodehouse; Saki, Dickens, Forster—in my last months at university the imitative reading widened naturally to Orwell, Aldous Huxley, John Milton, Shakespeare, Ortega y Gasset, soon to Nietzsche.

And on I read. For months, obsessively, and spent practically a year—all of 2010—in LaTrobe’s humanities library. Intellectual seclusion soon transformed, then funnelled, into an obsession with a single end in mind—to read until I could write.

A Moveable Feast in a few hours. Gatsby in a day. Brideshead in a weekend. Decline and Fall over and over again. These the writers who had come before, I was elated to be absorbing in youth whatever they conceived of as a ‘novel’—their subjects, their techniques, their tastes—so that I could one day conceive of my own.

Every great and original writer, in proportion that he is great and original,

WORDSWORTH

must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.‘

On the 21st of February that year, at the age of twenty-five, I was in my university’s library, intent on reading Waugh’s diaries. I went straight to that day’s date in his life—the 21st of February, 1927—when he was precisely my age. I still have not forgotten what I found. The entry read simply:

“It seems to me the time has arrived to set about being a man of letters.”

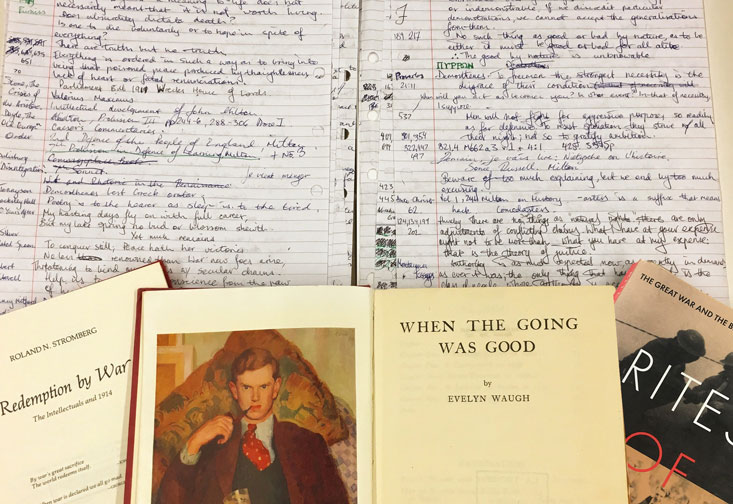

It is one of the few of my life’s innumerable signs that has never stopped driving me. The literary reading intensified. Waugh’s letters; Burgess’ essays; biographies of Hemingway; Greene’s autobiography—I pored over books in a dogged search for writing advice that had come from the pens or the mouths of the writers whose lives and work were awing me. In 6 months I filled my notebooks with 50 pieces of invaluable instruction that I hope I’ve now internalised.

Thinking back, I remember being particularly struck by half a line from Scott Fitzgerald’s letters: ‘When I decided to be a serious man…’ You can decide to become a serious man?!? And it’s serious men who write novels, right? Well then!

Henceforth consider me serious!

The most invaluable insight from this period of my reading came from a 1955 essay by Evelyn Waugh, here abridged and given at length.

‘The necessary elements of style are lucidity, elegance, individuality; these three qualities combine to form a preservative which ensures the nearest approximation to permanence in the fugitive art of letters.

The test of LUCIDITY is whether the statement can be read as meaning anything other than what it intends. Military orders should be, and often are, models of lucidity.

ELEGANCE is the quality in a work of art which imparts direct pleasure; again not universal pleasure. There is a huge, envious world to whom elegance is positively offensive. English is incomparably the richest of languages, dead or living. One can devote one’s life to learning it and die without achieving mastery. No two words are identical in meaning, sound and connotation.

INDIVIDUALITY needs little explanation. It is the hand-writing, the tone of voice, that makes a work recognisable as being by a particular artist.

Permanence is the result of the foregoing. Style is what makes a work memorable and unmistakable. We remember the false judgments of Voltaire and Gibbon and Lytton Strachey long after they have been corrected, because of their sharp, polished form and because of the sensual pleasure of dwelling on them. They come to one, not merely as printed words, but as a lively experience, with the full force of another human being personally encountered—that is to say because they are lucid, elegant and individual.‘

That summer, on a dissolute drive with my brother and two friends (the only time I’ve managed to get drunk three times in a day) from Munich through Nietzsche’s Engadin to Montenegro, I came up with a story. It was something about the abolition of night-time. Long had I now read; a serious man had I recently become.

I would see if I could now write.

Lucid, elegant, individual—I reached and strove for several months, took for the work’s title a line from Isaac Rosenberg and ended the striving with a prologue. The finished manuscript, pretentiously written on a typewriter, I immediately burned, and returned to studying and my notebooks.

Seneca and Erasmus both compare the ideal reading method to the activity of a bee, flitting through the garden of literature to take honey from as many flowers as possible. Another year of my own secluded flight led me to Byron, T.S. Eliot, Dante; The Greeks, Karl Kraus, Jonathan Swift, and soon—now above all in influence save for Waugh—to John Ruskin.

‘One of the chief elements of power in Gothic, and in all good architecture,

RUSKIN

was the acceptance of uncultivated and rude energy in the workman.’

My education now fell fully into Ruskin’s sagacious hands. The eloquence, the sensitivity! The insight, the genius! The autism!! Waugh once advised an audience of young writers to read a page of Ruskin a day. I began reading, at the very least, an essay of Ruskin’s a day:

‘But for us of the old race—few of us now left,—children who reverence our fathers, and are ashamed of ourselves; comfortless enough in that shame, and yearning for one word or glance from the graves of old, yet knowing ourselves to be of the same blood, and recognizing in our hearts the same passions, with the ancient masters of humanity;

—we, who feel as men, and not as carnivorous worms; we, who are every day recognizing some inaccessible height of thought and power, and are miserable in our shortcomings,

—the few of us now standing here and there, alone, in the midst of this yelping, carnivorous crowd, mad for money and lust, tearing each other to pieces, and starving each other to death, and leaving heaps of their dung and ponds of their spittle on every palace floor and altar stone,—it is impossible for us, except in the labour of our hands, not to go mad.’

Soon three awful but inevitable disintegrations in my private life necessitated a major departure. Living in Australia became—or had I subconsciously made it?—untenable. Trebly determined to become all that I was, I would crown my education in Europe.

I wandered around the cathedrals of England, scribbling beneath medieval stained-glass and Burne-Jones windows the notes for a new novel; strolled Lake District valleys writing into a tiny soft-covered Moleskine every fragment of my liberated curiosity. That notebook is filled with ponderings upon tombs and biblical quotations, contains much misanthropic vitriol—and almost no comedy.

Then I went for the first time to Venice with Ruskin as my guide.

‘The disciple of Ruskin rushed from one end of a city to the other comparing ceilings. His limbs were weary, his clothes were torn, and in his eyes was that unfathomable joy of life which man will never know again until once more he takes himself seriously.‘

CHESTERTON

This was precisely my Venetian discipleship. I spent entire days hunting down hidden windows and insignificant Bellinis—a month sighting any and all of the Venetian morsels whose study Ruskin had intimated would bring splendid enlightenment while saving me from moral ruin.

I met up with my brother in Florence and thereafter made little attempt to write as I drank the length of Italy, swam in several very famous fountains, crossed Sicily and languished in Portugal. Getting, because of port and ginjinha, no work done and nearing physical exhaustion, I retreated on Sam’s advice to Hoi An, Vietnam—the beginning of a Southeast Asian love affair which I still have not stopped pursuing.

I there sweated my way through three-quarters of a novel before abandoning it as poorly planned (and requiring the composition of prophecies in iambic pentameter). But, I felt, my conceptive power was growing. A very serious and complete novel was so very close to being mine.

I returned to Melbourne to work to save up a small fortune solely so that when a new story came I could return to Venice and really write. When it did, so I did: worked on the story while I chased windows and compared ceilings, then on to Florence, Rome, Naples, and Chamonix—where, halfway through this third attempt at writing a book, a young doctor walked into an alpine sauna and sowed for me an horrific seed—told me the lecherous story which had precipitated his solitary European honeymoon.

It was a conversational planting that soon would bear mighty fruit.

Again in Hoi An, Sam and I got caught in a Vietnamese typhoon for the week of my 28th birthday. We endured five days of third-floor isolation, surrounded by four feet of water with only the illiterate hotel staff for company. It was a typhonic encirclement that coincided with the airing of the finale of Eastbound & Down, the fourth season of which I to this day consider high comedic art.

Mortals falter. Kings act.

KENNY POWERS

And the mortal who acts?

Well that motherfucker becomes king.

As K.P. struggled against his freely chosen fate and coveted what he no longer wished to possess—as Danny McBride gibberished his way through eight episodes with an entirely original relationship to language and reality—and as its characters bought pet wolves for children and augmented their chins and hung brain while courting AIDS—I saw, as I began mentally and spiritually to age in that typhoon, that the sitcom, that funny entertainment—that effectively modern comedy—could all at once be moral, original, and hilarious.

I flew to New York to overwinter (what a word) while I finished the latest book and was reading as much Wodehouse as I could carry. I soon encountered an interview in which he advised the following:

‘I believe the only way a writer can keep himself up to the mark is by examining each story quite coldly before he starts writing it and asking himself if it is all right as a story. I mean, once you go saying to yourself, ‘This is a pretty weak plot as it stands, but I’m such a hell of a writer that my magic touch will make it okay,’ you’re sunk.‘

The latest story involved a young man digitally inventing a country so that he could stage a revolution in it—or rather in Australia’s media—only to come up against his best friend somehow staging a counter-revolution in the same made-up country. Amid that snowy New York winter I coldly examined its story on Wodehouse’s criteria. I was sunk. It was messy and political and more suited to a screen than a page. Though I remember it being my first time writing entire pages with sustained effort towards amusement, it was not an essentially funny book and was more satirical than hilarious, more sarcastic than entertaining. Beside Eastbound & Down it was fumbling, petty, and pretentious.

The sinking made me realise that after four years of attempting to become a serious man I was writing according to the taste of those authors whom I had initially worshipped. I had been ignoring who I was, forgotten where I had started. I was overlooking my Ruskin—attempting to repudiate entirely my rude and uncultivated energy. Indelibly an unserious person, frivolity was no longer to my mind a virtue; the Wikipedia article lay denied on a USB stick.

I was—despite the here-told years of literary labour—NOT a novelist attempting to write funny.

I was a comedian writing novels.

This, I saw in a flash, was the taste according to which I was to be relished. Mine ought to be novels written by a comedian, not comedies written by a novelist.

Testicles.

Snowed in, my reading intensified again and while watching for the first time the latest season of Arrested Development I came across two of the most invaluable and concise pieces of writing advice I had yet encountered:

‘Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.‘

VONNEGUT

‘All fine prose is based on the verbs carrying the sentences.‘

FITZGERALD

Upon my flash and upon mounting stylistic imperatives my work would soon become something new and entirely original.

Lucid, elegant, individual; my rude and uncultivated energy—character revealed and action advanced—verbs—and comedy!

In New York I was told two more horrendous adultery stories, both hilariously similar to the one I had heard in the Chamonix sauna.

The sowing of a second and third comedic seed, after one more change of scenery, they shortly would grow into a field of literary stalks.