The writerly adventures of Joshua Humphreys.

Before moving on to the 18 months which this essay covers I do have to go back six, for it was partly in order to begin a third novel that I hurried to finish and release the second.

In London in 2015 I showed to a friend who had never seen Seinfeld, Seinfeld. After two episodes the thing they thought funniest about it was George’s anger.

Anger as hilarity had never distinctly occurred to me. I had long considered it amusing: Kenny Powers’ tantrums are him at his equal best with his motivational speeches; my siblings and I had spent a childhood trying not to giggle whenever our father flew off the handle to stomp around the house in response to a minor infraction or impertinence. The high points too of Fawlty Towers were built entirely on frustration.

What, I that evening thought, if a comedy novel were based entirely on anger?

Before leaving for Thailand I bought a biography of General Patton to take with me and was reading it through my last British days while watching a screaming Costanza in the evening. General Patton, about whom I had known only what was shown in the 1970 film, quickly revealed himself as an exemplar of a man.

A giant of a former, greater, age—a man extinct, the last in a continuous line stretching angrily back to Achilles. Yet he had lived only 70 years ago, commanded in the same war that my grandfather and his brother had fought. What if he were reincarnated, his Nazi-quashing anger pointed down at the pettiness of modernity and at the smallness of our lives?

He would constantly be at GLC levels!

Could their personalities then be combined, the two Georges—Patton and Costanza? Certainly not though in a story about a grumpy old man. That had been done to death.

But what about an angry young man?

Clint Eastwood at 85 had a sound right to complain about exponential change. But a 30-year-old with no justifiable framework for disgruntledness—a person perfectly in his time but in no way of it—supposed to be in the joy-throes of equality and diversity and other ideological slogan-words, but preferring without question what has perfectly fulfilled humanity’s sense of purpose for longer than 2000 years?

These, a host of worthy literary themes: anger, change, nostalgia, action. So a new novel began to grow.

Three months later and I had finished Exquisite Hours and resolved to take the biggest gamble of my life. In Bangkok waiting out a Christmas flight, I looked over the few notes that I had taken for this next novel and knew two things: Melbourne would be the theatre for my main character’s anger, and he needed somewhere and something to contrast it to.

Melbourne being above all tame, I needed somewhere wild. I was in Thailand but that didn’t quite have it. Even its more remote islands are repositories for barbecue buffets and snorkelling parties—hardly wildernesses. I looked on a map and at the countries surrounding me.

Bonobo’s can’t clap.

Vietnam I had been to four times and felt it more rural-industrial than riveting. My brother told me Laos was sleepy. Burma was not then easy to visit and of Cambodia I knew only a recent genocide and its American pounding in their war on Vietnam. Sam told me of Siem Reap’s street parties, its tuk-tuk mafia, its magic mushrooms—and its 1000-year-old temples covered in jungle.

There was even a $4 wooden slow-train that would take me there…

With two histories on my lap I rode from Bangkok to the Cambodian border and knew before I had arrived that I had my location. Recent conflict, a habit of cannibalism, belief in magic, and—and this gave me the entire story in a moment—looters.

Thai mercenaries were renowned for crossing into Cambodia and racing to its temple-cities in order to buzz-saw friezes from their place to deliver them to black-market antiquities dealers. My nameless angry young man had his Cambodian vocation.

Protecting what is ancient and vulnerable from what is new and greedy. He would live by and for protecting Siem Reap’s ruins from looters and, torn from those adventures, return home to Melbourne to do anything but that.

‘Angkor, as it stands, ranks as chief wonder of the world today, one of the summits to which human genius has aspired in stone.’

SITWELL

It took all day to get to Siem Reap but the following morning I headed out to its ruins. The vast and quiet tidiness of Angkor Wat, the roots and strangling vines of Ta Phrom—they were spectacularly impressive and immediately I set to work building a story around their forceful preservation, writing in the mornings and carousing in the evenings.

Perpetually hungover, I one morning craved my traditional medicine and remembered that my brother had told me that though he had gotten horrible food poisoning from a Burger King in Phuket he had in fact had the best KFC of his life in Siem Reap. Eager for its fried elixir to impress and cure me I zombied into the only KFC in Siem Reap. 6 hours later, walking from town to my hotel, I started cold-sweating and suddenly could walk no further without throwing up on the street.

Three days of desperate convalescence followed, throughout which I actually thought I was going to die. Were it not for a friend I made there, who works as a tour guide for elderly Danes in Central Asia—and who brought me litres of gatorade and enough drugs to kill all that was evil in my stomach—I might have shrivelled into a diarrheic mummy.

When on the fourth day I could sit up straight and type, I emailed my brother and asked him if he had ever had death-inducing food poisoning. His response was, “Remember I told you about the KFC in Siem Reap!?” Evidently he had in fact had the best whopper of his life in Phuket.

If you take anything away from this essay,

please let it be to not eat KFC in Siem Reap.

When at last I was unchained from the toilet I headed for the final temple on my To-See list. Upon spying Preah Khan’s magnificent eastern entrance through the forest my mouth opened. It did not close until I left the complex, three hours later.

It is, with St Mark’s Basilica, the most exhilarating edifice in the world. Byron might have meditated for a time upon the colosseum and Keats for an age upon his Grecian urn. Neither come close to the philosophical wonder and existential melancholy which emanate from the crumbling stones of Preah Khan—from the turquoise moss and purple-flaming foliage carved upon its columns, from the guardians of holy places serene and ugly in their niches, from the fallen lintels creeping with vine and from the thousand smiling apsaras holding in their hips the rhythmic dance of Siva, destroying and creating in derision at the shortness of human time.

So incomparably impressive are the ancient ruins of Cambodia that I’ve just composed a separate photographic essay dedicated to their splendour, replete with my Siem Reap travel tips:

Whole Enjungled Cities

When I returned to Bangkok I was drawn to all the old Southeast Asian travel books I could find and watched over and over again The Outlaw Josey Wales and The Man Who Would be King.

It was adventure the world now lacked.

It was adventure my main character would be living.

It would be the loss of it that he furiously laments when forced to return home.

Back in Melbourne for the three months it would take to properly launch Exquisite Hours, I was dismayed by the still-shrinking smallness and the creeping digitization of existence. I had not been home in two years. In so short a time it had become impossible for a person of artistic temperament to thrive there. So between promoting and signing books I catalogued the grievances which my main character might have against the place.

Having bought myself another season I first returned to Cambodia to further research and build the new book’s story then went on to Vietnam to procure a motorbike and ride the bottom half of the country from Saigon to Hoi An. I rented a house with my brother and attempted to find a balance between promoting past books and writing new ones. It is a balance I still have not been able to reach.

The time needed to devote to making money from writing is now much too great to enable me to write new ones. I have a fifth comedy novel, the purest and funniest yet—veritably a sitcom in prose—ready to write and in the coming months shall have to give up social media entirely in order to write it. With fully the intention of getting that novel published and made into a TV show, I shall in September be moving for one final season, and allowing only those who would become patrons of the arts, patrons of the comedy novel, to be a part of my creative process.

Each day filming videos before working on the new story, I quickly needed to break the monotony of promoting and writing. Quite randomly, running along the beach one day, I had an epiphany. As well as comedy novels, I thought that maybe I could give people what had made their writing possible in the first place: Venice.

I could give them Venice.

Not the Venice of gondolas and gelato and the Bridge of Sighs, but the real, medieval Venice—she whose art and architecture had formed my sensibilities, the artistic and moral lessons derived from her history that had enabled me for so long to wander the world with childish wonder while living and working as an artist.

So I began in the afternoons to formalise what I knew of her, and to turn the city’s palaces and canals into what would become The Stones of Venice Tour.

’It’s a curious fact that you cannot work out a continuity at a desk—you have to move with your characters.‘

GREENE

Literally pacing back and forth in our Vietnamese front garden, working through the novel scene by scene until it made not just sense but a whole, l came up with a cast of characters for both Siem Reap and Melbourne and set them on their respective adventures.

Writing a book I myself wanted to read, I at every turn sought to inject anger, preposterousness, and audacity, into its story. As well I wanted to explore the idea that “progress” might in fact mean “destruction”, and that in racing to remake the world in the image of our selfishness we might actually be rendering it hostile to true adventure.

So my angry young man was to be pulled out of his Cambodian happiness by news of his father’s grave illness. Returned to Melbourne, he would live in his childhood home before his abrasiveness meant he would have to move into his grandmother’s nursing home.

In need of a fortune to cure his father, his thorniness would render him unfit for employment and while pointlessly applying for a bank loan he would get wind of a stash of gold belonging to Australia’s 40 or so billionaires. Seeing in that immoral wealth an adventure reminiscent of his Cambodian exploits he would resolve to steal it, and would reunite his Cambodian soldiers in Melbourne to do so—all while trying to revive a high-school romance whose intensity he has grossly misremembered.

I carved these adventures into an enclosed and ludicrous narrative and in the process struck upon my main character’s name. Called after that first tragic Greek hero, Hector, his pertinent surname became early in its conception the novel’s title:

GRIEVE.

After three months of pacing I had the entirety of the book’s story and now needed two months to write the first two drafts. This is Bruce Chatwin, he who posited that the ultimate question was the nature of human restlessness:

‘American brain specialists took encephalograph readings of travellers and found that changes of scenery and awareness of the passage of seasons through the year stimulated the rhythms of the brain, contributing to a sense of well-being and an active purpose in life. Monotonous surroundings and tedious regular activities wove patterns which produced fatigue, nervous disorders, apathy, self-disgust and violent reactions.‘

However beautiful and romantic was Hoi An I needed a change of scenery, and it just so happened that a friend had a spare room in Battersea. So it was back for a London summer, en route to Venice, to start writing Grieve.

Setting to work immediately I wrote its Cambodian open, 18,000 words, in a week. These opening chapters still are my favourite of all the sections in my books. Hector Grieve in Cambodia—gallivanting on horseback, shooting guns, giving martial speeches to his squadron of orphans, drinking hallucinogenic whisky by the bottle, claiming to be the greatest lover that Angelina Jolie has ever had.

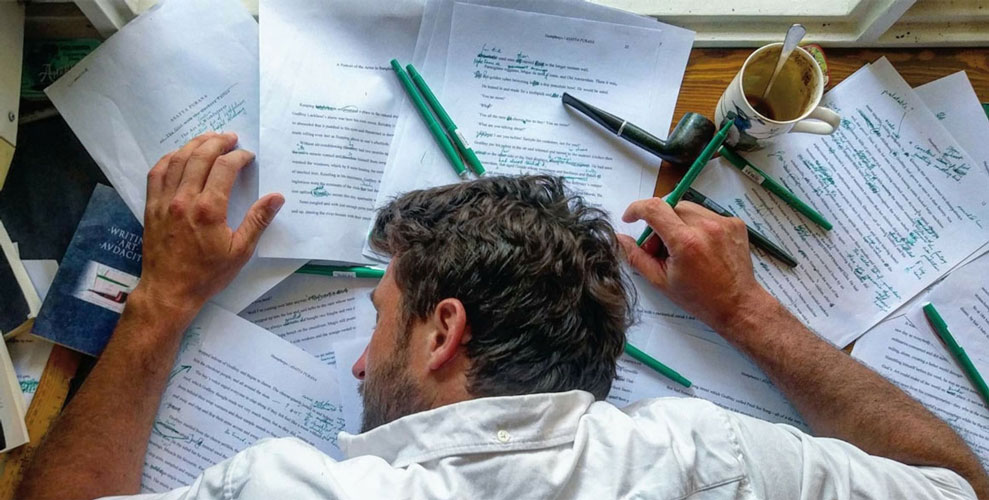

There followed one of the most intensively productive periods of work that I’ve ever managed to pull off, and one filled with the same joyless monotony with which Hector was soon having to deal in Melbourne.

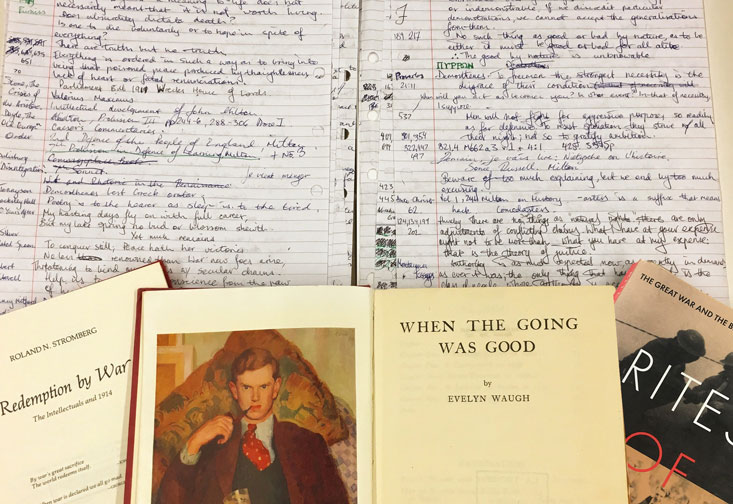

My morning writing routine had been transplanted to a place where I had no motorbike, no beaches, and rarely even the sun. In my afternoons I was reading Osbert Sitwell’s Escape With Me!, Robert Byron’s Road to Oxiana, Casanova’s History of My Life—none works that enable one to sit contently inside for weeks on end.

‘Writing is the art of applying the ass to the seat.‘

PARKER

Luckily I needed this frustrating London modernity as fodder for Hector’s fury. Seamlessly I could transpose self-serve checkouts and parking fines and conversation-in-hashtags from Battersea to Melbourne and in six weeks I finished three-quarters of the first two drafts and took to Venice a 322-page manuscript.

While in Cambodia I had been contacted about my work by a woman who runs Balinese wellness retreats. Inspired by my plan for an art and history tour of Venice she decided to hold a retreat in that floating city and asked if I would incorporate the tour into its programme.

I won’t here go into detail about the psychopathy to which I was there both witness and object, but from its first morning on that “retreat” (an apt Hectorian word) formed the basis of an even newer story—one that would grow so preposterous as to end up practically uncooked as the plot for my next novel.

But, The Stones of Venice Tour!

Each morning rising before the sun and the tourists, I spent a month walking individuals, couples, pairs, groups of friends, around the most beautiful city in the world—empty because of the early start and my long-grown knowledge of its tiniest alleys.

From the city’s beginning as a salt-farming village to its growth by trade and conquest into the richest and most powerful city in the world—to its several apotheoses of glorious art and its constant creative genius, the two-morning tour passed on to dozens of new students the lessons that Venice and Ruskin had taught me.

As well as having St Mark’s Square at dawn for my office that September, the tour was lauded by several people who took it as the greatest experience of their life.

For me that sunlit Venetian month was both a privilege and a joy. I was able to pass on to so many people what had given me so much delight and nourishment and to revive in them that love of culture which alone makes life worth living.

Presently putting Ancient Greece through the same structural and narrative process, I plan on giving a Stones of Athens Tour next year, and to pass on to those who attend the unequalled philosophy and epic history of what many consider to be the first and highest pinnacle of the human mind and heart.

After Venice it was back to Southeast Asia, first to Cambodia to rewrite Grieve’s opening in situ, then to Thailand in order to fly to Melbourne for Christmas. Bonobo’s won’t clap and spending only two weeks in Bangkok I met an expat who lived in an apartment in my favourite corner of the mega-city, and hearing from him of how easy and affordable it was to do so I sensed a possible change of direction for the coming year.

At home I finished and rewrote Grieve’s much longer Melbourne section and found the book’s epigraph in Byron’s great satirical adventure: “I want a hero, an uncommon want,”—for a hero Hector Grieve was, and in a very unheroic age. I got in contact with some Bangkok real estate agents about maybe renting an apartment there. They sent pictures of condos and most were mouldy and among ramshackle slums and traffic.

But one of them…

One overlooked a canal and two temples, had a picturesque swimming pool, appeared even to have a rooftop garden—and was in my favourite corner of one of my favourite cities. I took the Nietzschean line, the Montrose line—now the Hector Grieve line—and said Fuck it.

I told the real estate agent I would take the apartment, transferred the deposit, and with all the excitement of a chubby child at Christmas I on New Years’ Eve flew to Thailand and was in my new home two days later. January 2017 is the last time I felt this level of enthusiasm for anything.

Though the apartment was small, 30 square metres, its building rendered the move beyond worthwhile. The view from my bedroom and kitchen was indeed of a winding khlong and of the glittering golden roofs of two temples. The pool was long and all day in the sun and almost always empty of people, and the rooftop! I won’t here describe its splendour but at 40 floors up and looking across at Krungthep and the Chao Phraya river, or back over the canal and its temples, it so drew me that I watched the sunset there every night for six months.

Bangkok then became another corner of the world to which I can always happily remove and one in which I feel at home and am productive.

I’ve spent a full fifth of my last five years there and hope in 2021 to add a Bangkok tour to my repertoire, the history and architecture of that city being equally as fascinating and exquisite as are those of Venice and Athens.

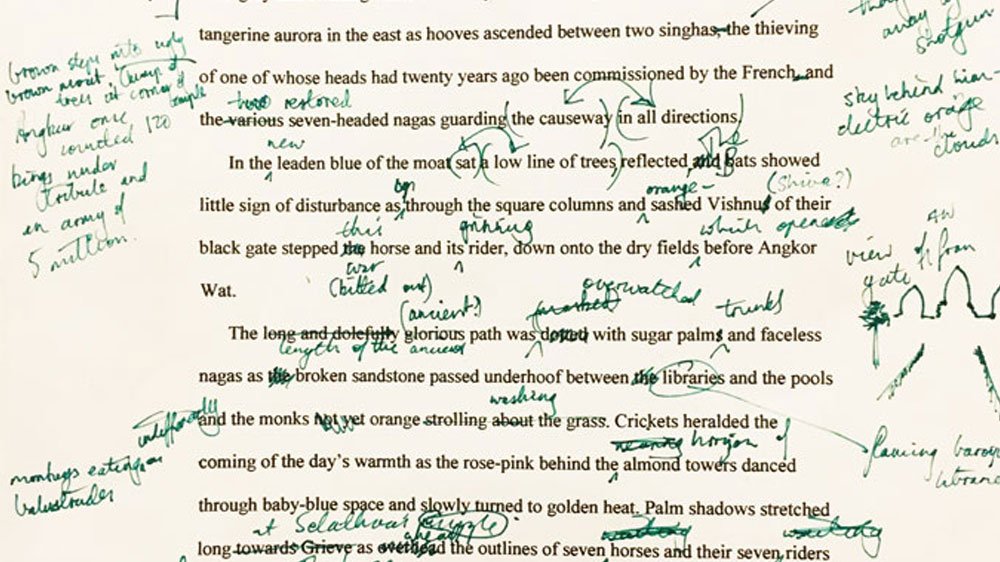

It was in this new Thai corner of my world that I laboured over finalising Grieve’s manuscript. The sun rose on my bedroom window and again I had chanced upon a place perfectly suited to my routine. At a kitchen table acting as my desk I spent two months of mornings rewriting and rewriting and rewriting. (I twirl my pens when I’m working and before moving out of that apartment I had to repaint the kitchen walls to cover the flecks of green ink.)

By midday I could rewrite no more and would walk along my favourite chaotic street for lunch then work in the pool, manuscript pages tucked under my laptop set at its decked ledge, retyping the morning’s amendments.

Then I would walk to the canal, where a kind of gangplank served as my jungled running track, and return in time for 7-11 to start selling liquor (they’re prohibited by law from doing so between 2 and 5pm) then walk 24 flights to the rooftop with a speaker and my pipe to watch the sun set in one of the most consistently magnificent vistas to which I’ve ever lived near.

‘It is meant to be a little quietly facetious upon every thing. But I doubt whether it is not—at least, as far as it has yet gone—too free for these very modest days.‘

BYRON, on Don Juan

In the evenings I read Byron in all his forms and re-read lives of Patton, working towards making my Hector Grieve as effortlessly offensive as possible while ensuring he kept the charm and audacity of which men of his ilk seem uniquely capable. I was struck then, and am still struck now, by a sentiment found in his writings which appears common to most who have reached the pinnacle of their vocation. The following is General Patton:

‘The most vital quality a soldier can possess is self-confidence—utter, complete and bumptious. You can have doubts about your good looks, about your intelligence, about your self control; but to win in war you must have no doubts about your ability as a soldier.‘

While this is F. Scott Fitzgerald:

‘A writer like me must have an utter confidence, an utter faith in his star. It’s an almost mystical feeling, a feeling of nothing-can-happen-to-me, nothing-can-harm-me, nothing-can-touch-me.‘

Interchange the word soldier for writer in either and you have, I believe, one of the key lessons by which life must be lived.

By story’s end I had made Hector both a foolish romantic and a 21st-century Robin Hood—and into a much-needed antithesis of modernity.

He has never heard of yoga nor owned a mobile telephone; he believes that what is old should be respected and what is great should be striven for; in the freedom of the individual and that the individual should freely choose noble servitude; he values action for its own sake and questions not why or how he does things. These ideals are found in Nietzsche’s summing-up of the civilization that was disappearing with his sanity, and come more succinctly from General George S. Patton’s mouth 50 years later:

‘War is the only place where a man really lives.’

‘Do not take counsel of your fears.’

‘One has to choose a system and stick to it; people who are not themselves are nobody.’

‘I am sure that if every leader who goes into battle will promise himself that he will come out either a conqueror or a corpse he is sure to win.’

‘Accept the challenges so that you can feel the exhilaration of victory.’

‘Do your duty as you see it, and damn the consequences.’

‘Anyone, in any walk of life, who is content with mediocrity is untrue to himself.’

I ended up putting one of his lamentations alongside Byron’s as dual epigraphs:

“I am different from other men my age. All they want to do is to live happily and die old. I would be willing to live in torture, die tomorrow, if for one day I could be truly great.”

Though it might sound difficult to make a such a character funny in a comedy novel sense, by the absurd rudeness of Hector’s insults, by his carrying in a gunless country an antique ivory-handled revolver, by his not giving a flying peacock’s fart for modernity, by his almost 400 uses of the word ‘fuck’—and by the tininess of his fuse and that original Costanza temper—I do believe I succeeded.

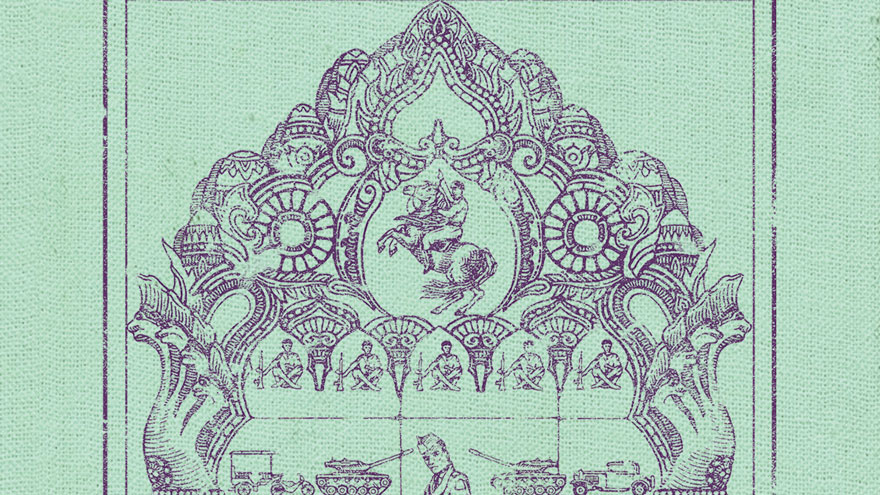

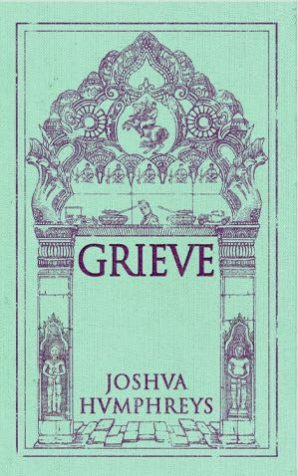

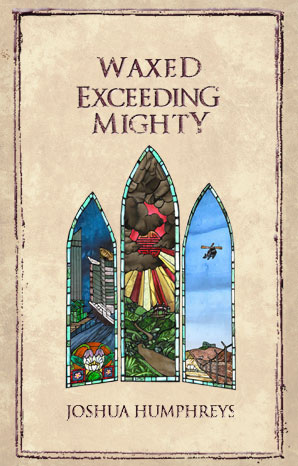

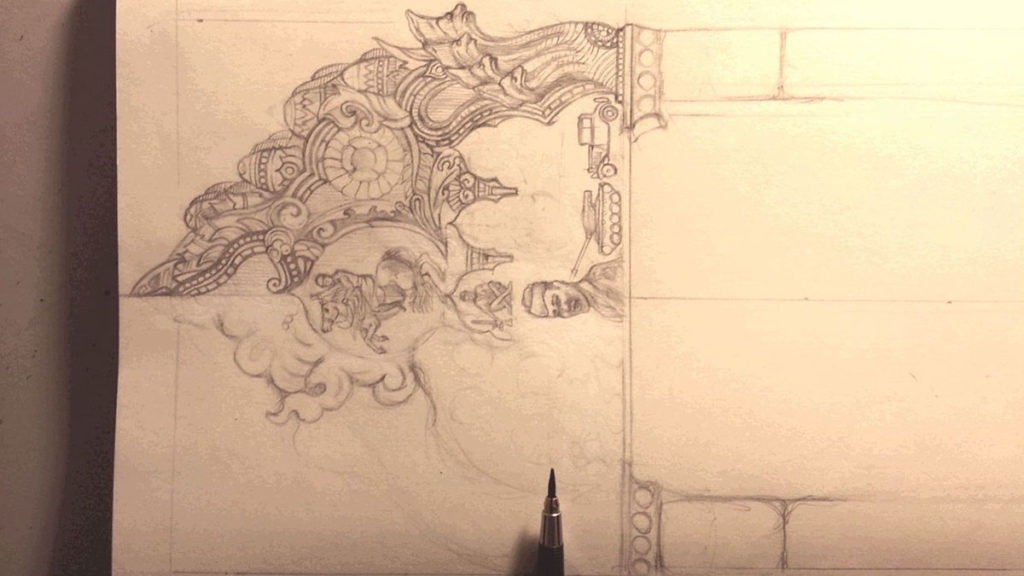

Again I commissioned a cover from my brother and asked him to base its style on the Khmer art and architecture found on the temples of Siem Reap—those whose splendour Grieve is forced to leave behind and whose loss he so desperately laments.

That cover, which integrates several elements of the story, is the best thing my brother has yet done for me and here deserves greater attention.

The two dwarapalas, ‘guardians of holy places’, are taken from extant statues, one at Preah Khan and one at Banteay Kdei. The seven-headed nagas on the capitals can be seen on the pediments of Banteay Srei and on the ends of most of the balustrades guarding Angkorian causeways.

The central figure is Hector on Selathoa, his favourite horse, wearing his Patton uniform—modelled on Jacques Louis David’s Napoleon and surrounded by Garuda feathers. The tanks, the tuk-tuk, the Citroen C6, commemorate the book’s opening, in which his squadron successfully repels a Thai tank raid on Angkor Wat. They flank in military uniform Elvis, the name and dress of Hector’s aide-de-camp and closest friend in Cambodia. The five cross-legged soldiers are Hector’s orphans reposed as the rows of monks into the walls of the classical temples.

Its purple and light turquoise are very close approximations of the shades which the moss and the lichen at Preah Khan take through the wet season. Had I a home I would have the cover enlarged and mounted on a wall as a testament to Sam’s talent and as a reminder of what now seems a golden era of my working life.

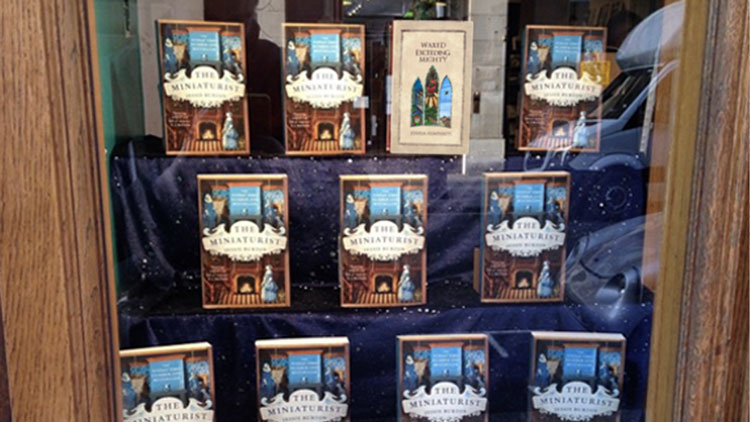

I had to do a visa run from Thailand and went again to Cambodia to give one final touch to the novel’s open and to produce material for the book’s launch inside the very temples in which its action took place. There I loosed Grieve upon the world and opened it to pre-orders. In a week it sold twice as many copies as did Exquisite Hours in its opening weekend—without my having to dress up as a mermaid.

Having launched my career by writing a novel that everyone wanted to read, I had finished and released a book that I wanted to read.

And it too had a place and an audience in the world.

The books coming all the way to Bangkok for me to inscribe and then send out to readers, I used the 6 weeks they took to arrive to give a second run of The Stones of Venice Tour and returned by way of Jerusalem.

Coming home to box upon box of unsigned comedy novels, I spent a week numbering and inscribing them and again had to order more to cover a surplus of interest. Thankfully I ended up dressed as a mermaid anyway—reading the book underwater purely out of gratitude to Grieve’s popularity.

There is no conveniently sharp break, as there had been between Grieve and Exquisite Hours, between this book and the next. I had settled into a writing and releasing pattern that seemed as though it had simply become “my life”. Nor was there upon finishing Grieve an overlap in novels needing to be written.

Hector’s story was the last time that my own adventures, and not an ordeal (or indeed several ordeals combined), inspired my work. Its writing seems now, enchained in middle age by a frightened world, to have been a joy rarely afforded most artists. But I felt it to be as such throughout its creation and for that I sit here grateful. I only hope that soon something like a bank vault filled with billionaires’ gold makes itself known to me, and that like Hector the nostalgia for an audacious past inspires me to steal it.

In the wake of the book’s release I was still living in Bangkok and had been slated to work again on a wellness retreat, this time in Bali, for the same deluded guru as in Venice but—

I’ve just realised that I’ve largely omitted my personal life from these otherwise personal essays. I shall give but two amorous details, and in the next essay relay more of the chaos that has been for almost a decade my love life, as the next two books would spring directly from it.

In Bangkok I had gone and gotten myself a girlfriend, a Canadian who lived in Da Nang. Upon learning this, the wellness yogaclown informed me that she would no longer be employing me on her retreat.

Fired for having a girlfriend, in an instant all the personal and spiritual ridiculousnesses of that first Venetian wellness retreat became fair game for comedy novels. The delusion and manipulation that nourish and run “wellness retreats”, which I had hitherto merely stored as terrifying memories, were immediately decided upon as the material for my next book:

The story of a struggling artist unable to make enough money to continue working, employed by a flourishing con-woman whose sageful

masquerading makes her debilitatingly lonely.

But it would be another year,

and the spontaneous germination

of a Shakespearean romcom

—veritably a whole interceding

fifth act of Josh Write Book—

before I would sit down to write it.

GRIEVE—the story of a hellraising soldier of fortune forced to leave his life of adventure for the frustrations of modernity—is available direct from its author, who occasionally refers to himself in the third person.

At its lowest price, and inclusive of shipping, you can purchase a copy directly from Joshua Humphreys [ here ].

And do feel free to contact him (or even me) with questions about writing, about Venice, or about any of the above, at: pigeonry@joshvahvmphreys.com